By Christophe Huette

Freedom 72, no. 8

April 23rd, 2011

“I enjoy making revolution! I enjoy going to football!” (Antonio Negri).

The relationship between the “Beautiful Idea” and the “Beautiful Game” is a complex, frustrating and fraught one, but at its intersections are where some of the most interesting dialogues in the anarchist movement are located.

Football and anarchism developed roughly in historical tandem, with the Workers movement formalising around the same time as the British Football Association (FA) was founded in October 1863. By 1871 we have more or less the modern game with the regulations established (no hands in the outfield, no shin kicking), but they are relatively simple and few, leaving loads of room for creative innovation. This is what makes football “beautiful” and unpredictable, and there have been many attempts to stifle that over the years, with the low score rate leaving plenty of scope for sensational surprise outcomes and luck. Football is the sport like no other, where the underdog can flourish.

And here we see possible comparisons with anarchism: “The ball has no attribute of power. The passer does not own the ball; he possesses the ball in the sense of Proudhon. The passer remains the master of the act. As in libertarian society, he is free to do what he wants. However, he cannot exist alone, he cannot progress alone, and he cannot survive alone. Here is where the principle of mutual aid comes into play, as explained by Peter Kropotkin” (Wally Rosell from Albert Camus, the Anarchists and Football).

Not that the anarchist movement embraced the game of two halves with universal love and affection, as this rant from Germany in the 1920s shows: “May God punish England! Not for nationalistic reasons, but because the English people invented football! Football is a counterrevolutionary phenomenon. Proletarians between the age of eighteen and twenty-five, i.e., exactly those who have the strength to break their chains, have no time for the revolution because they play soccer” (Free Workers Union Germany).

But of course we also see the viral rise of capitalism, which wasted no time in taming the game. So whilst the working classes tended to play and embrace the game, it tended to be administered and financed by capitalist industry. (The toffs tended towards rugby, which was non-professional and a suitable recreation for those whose purpose was to administer the empire.) Standardised measuring, bookkeeping and the strict invigilation of time have been cited as examples of the influence of the emergent bourgeois-capitalist culture. But “[w]e don’t want to consume football, we want football to be ours! It was ours before capitalism took it away!” (Danilo Cajazeira, founding member of Autonomos FC).

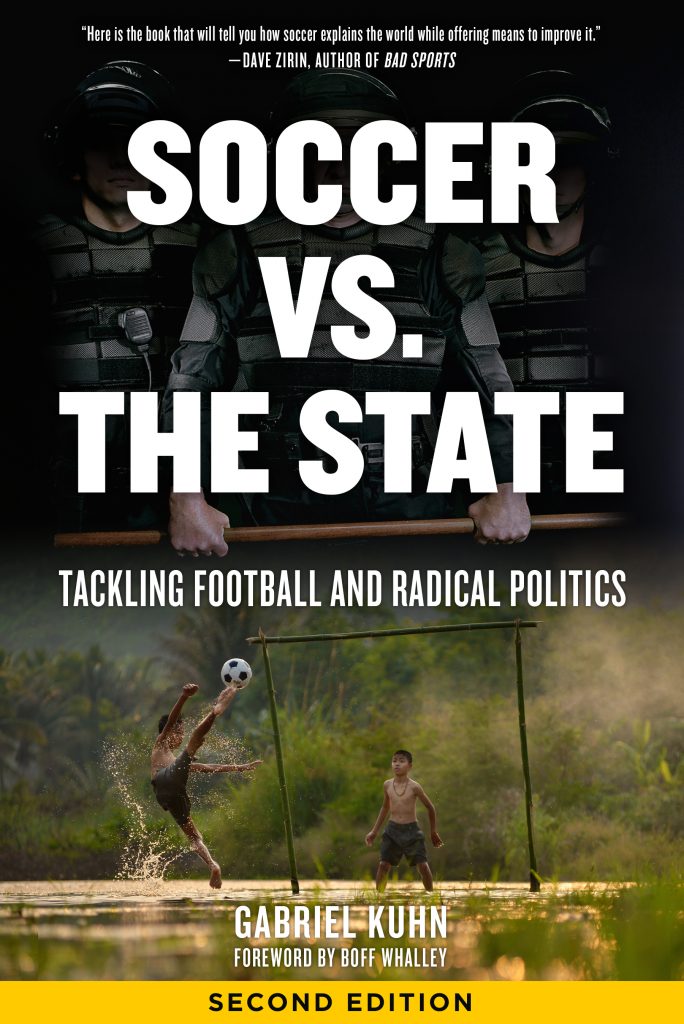

Kuhn’s wonderful, accessible and necessary book develops football’s beginnings through the tribalism, sexism (women’s football was banned by the FA from 1921 to 1971) and bigotry that qualified the game during much of the 20th century. But the bulk of the book concerns the radical responses to this. Full of radical debate and loads of interviews and source material, Soccer vs. the State is fucking good!

“Football has proven time and time again that it contains a magic, immensely powerful element, not unlike the stuff that religions are made of”.