By JJ Amaworo Wilson

JJ Amaworo Wilson

July 17th, 2015

Elite sport has a lot to answer for. Rabid consumerism, blind nationalism, rampant cheating, endemic corruption. Just in the last couple of years we’ve witnessed FIFA’s corruption scandal, mass protests in Brazil against expenditure on huge stadia, and the saga of Lance Armstrong. And don’t get me started on the feudal world of professional boxing.

And yet … and yet … like a 300-pound wrestler in spandex, sport holds millions in its enthralling grip – me included. The greatest of our sporting men and women – our modern-day gladiators – are feted as gods, and their skills transport us to a place of dreams.

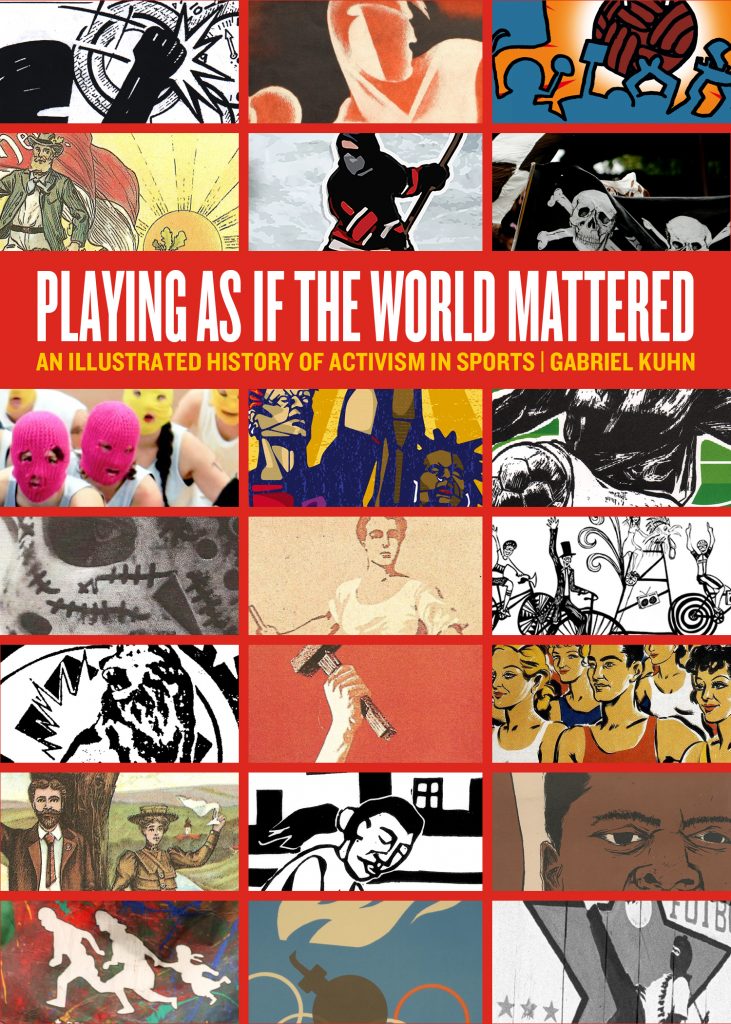

Gabriel Kuhn’s Playing as if the World Mattered: An Illustrated History of Activism in Sports (PM Press, 2015) is a potted history of activism in pro and amateur sports. At 158 pages, it’s as slim as the end of a snooker cue, and half those pages consist of reprints of old posters, illustrations and photos.

The book is all about breadth rather than depth. It contains very short essays on movements, organizations, heroes and key moments in sports activism. The usual suspects are here – Jesse Owens, Jackie Robinson, Muhammad Ali – but Kuhn also crosses borders to look at movements in Apartheid South Africa, Indonesia, Europe and elsewhere. He highlights several stories that are in danger of slipping out of collective memory:

*The wrestler Werner Seelenbinder, banned in 1933 for refusing to perform a Hitler salute, was executed in 1944 after his heroic stand in the underground resistance.

from http://www.laprogressive.com

*In Mexico, 1968, when Tommie Smith and John Carlos stood on the Olympic podium, shoeless, and did the Black Power salute, the Australian Peter Norman, who won Silver, wore an Olympic Project for Human Rights badge in solidarity. He was never selected again by the Australian athletics board. Smith and Carlos remained lifelong friends with Norman, and just as Norman had supported them, so they literally supported him in death, serving as pallbearers at his funeral in 2006.

*Brazilian soccer player Socrates spearheaded the Democracia Corinthians movement, 1982-84. The goal (excuse me) was to democratize soccer by involving the players in all decisions including training methods, team selection and transfers, and to thereby challenge the military regime. Alas, the movement fell apart when Socrates left to play in Italy, enraged by the military running his country.

*Argentina’s World Cup winning coach Cesar Luis Menotti refused to shake hands with junta leader Jorge Videla after Argentina’s victory on home soil in 1978.

Such stories made this fine book worthwhile for me; that, and its useful reference sections.

One drawback is that the book lacks a sense of how these movements and people fit together. What did Muhammad Ali learn from Jackie Robinson? What was the link between Mussolini’s use of the 1934 World Cup as a showcase for Fascism and Hitler’s use of the 1936 Berlin Olympics for Nazism?

The other drawback is that it’s very light on women’s struggles in sports. Billie Jean King and Martina Navratilova are barely mentioned in passing.

Near the end, Kuhn writes, “What would an ideal world of sports look like? There would be no more superstars, no more billion dollar contracts, no more endless hours of televised sports …” (p. 155) Impossible to imagine? So was the end of slavery. So was women’s suffrage. I adore sport, but this slim book made me question how elite sports are run and what they really stand for. And that, for me, is priceless.