By Rachel Swan

East Bay Express

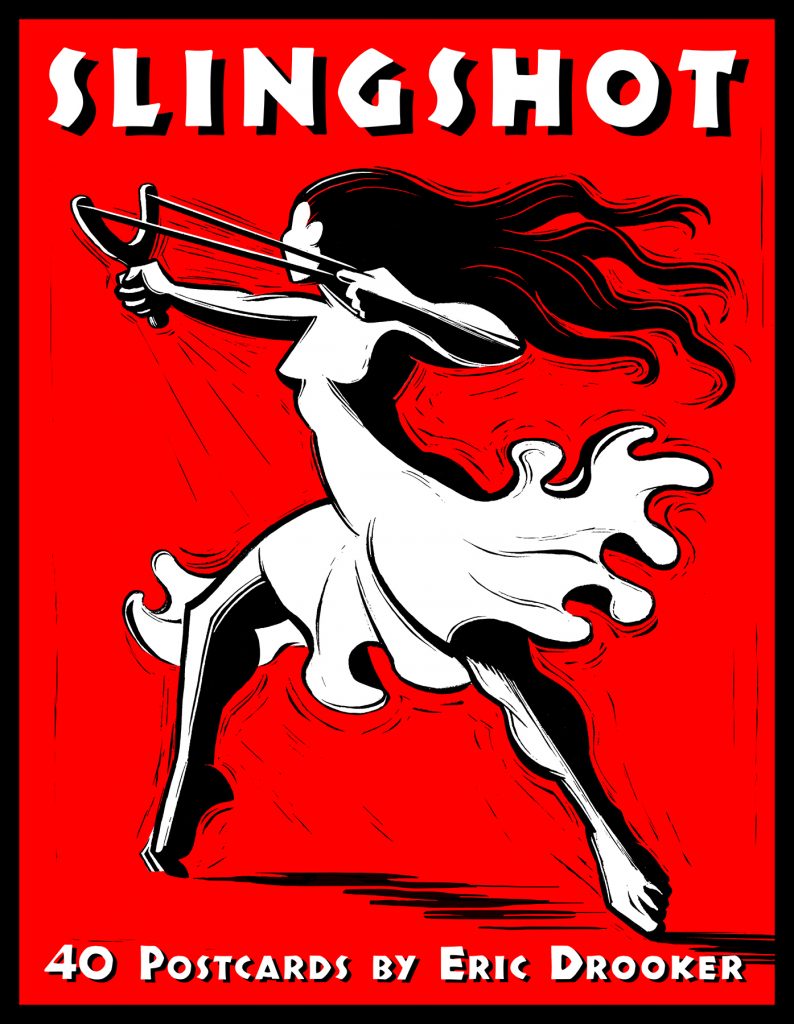

Although Eric Drooker has lived and painted in Berkeley for the last ten years, nine times out of ten his dreams still take place in New York City. Drooker grew up in a seventh-floor apartment building near Manhattan’s Lower East Side. He’s famous for drawing cityscapes that press against the edge of the page and crush out the organic forms: bruising, two-dimensional illustrations of steel-framed skyscrapers, subways, soft drink billboards, electric nightclub signs, tenement fire escapes, the East River, and the Williamsburg Bridge. These drawings have a very specific time and place (Brooklyn or Manhattan, usually in the 1970s, almost always the same view), but they employ metaphors that anyone could pick up and understand. His mass-produced poster art, some of which is collected in the new postcard book, Slingshot, operates in much the same way. The images might have a specific origin and intention, but what they depict — a dove flying over the subway train, or a barefoot woman kicking a policeman — is universal and eternal.

Drooker’s images have more currency than his name. Born to a family of artists, Drooker was always looking at things from a slightly different angle than everyone else. He also was a troublemaker who liked to throw shit out of the window of his high-rise: firecrackers, cherry bombs, water balloon condoms, bottles of ketchup, pee-pee, a balloon filled with pornography one New Year’s Eve, and once, a container of hot water on a cluster of policemen below. Drooker wasn’t into superhero comics, but did gravitate “to all the really perverted shit,” like Zap and R. Crumb, who taught him all about human sexuality. He sketched his first cityscape at age eleven, and it was just a slightly cruder version of the ones he does now. He could get inspired by anything: a ketchup bottle splattering on the sidewalk, the city skyline, two bums warming their hands over a garbage can fire, a red umbrella that flew in his field of vision while he was sitting outside a squat in Amsterdam, smoking a joint.

In the ’80s, Drooker parlayed his rebellious personality into activism, and became a tenant organizer in the Lower East Side. He made posters and pasted them all over New York City, eventually catching the eye of Beat poet Allen Ginsberg, who would peel the images off lampposts and the sides of buildings and collect them. The two first hung out at length in August of 1988, during the Tompkins Square Park Police Riot. (Their friendship eventually led Drooker to illustrate Ginsberg’s poetry collection Illuminated Poems.) Drooker’s protest images — of a small tank going up against an army of musicians with trumpets and drums, of a woman using a mallet to bust through a brick wall, of Mumia Abu-Jamal pecking at his typewriter through the bars of a jail cell — have become iconic. He gives them away to activists whose causes he believes in. Many people have Drooker images adorning their punk show fliers or even tattooed on their bodies, and might never know it.

He lived for roughly twenty years in the same tenement building on East 10th Street, first in a storefront downstairs that flooded when a pipe burst (and became the inspiration for his noir-ish 2002 graphic novel, Flood), then upstairs in an apartment that opened up when the previous tenant died of AIDS. During that time, Drooker had been designing covers for The New Yorker magazine, which he does to this day, to help eke out a living. In the old days, he would finish a painting and walk over to the office on 42nd Street, flirt a little with the art director, and see if it sold (it usually did). Later, after moving to the Bay Area in 2000, he’d mail the original over. He didn’t get his first computer until 2004.

His current studio sits in a downtown Berkeley office building where he’s surrounded by insurance salesmen, attorneys, and even a condom distributor. There’s a large rock garden in the atrium with pebbles and tropical-looking plants. His studio walls are adorned with pictures — the oil paintings and pastel drawings of human figures, the self-portrait in a New York subway station, an image of one of his recent New Yorker covers with monkeys and a toucan gazing out over a bridge in New York City. Drooker always has his current sketches on the wall — last year around this time he was working on a classical image of a man with a bull head and a bayonet that became the painting “Moloch.” Free jazz plays from an Internet radio station, and a gymnast’s rings hang from the ceiling. Stacks of his new postcard book, just released under the wing of Oakland’s new independent publisher, PM Press, lie in a box. The images included are among the most provocative in Drooker’s oeuvre: a screaming infant; a hand drowning in a polluted harbor; and of course, the cover graphic of a wild-haired woman in a ballet dress, brandishing a slingshot.

Drooker likes for his work to be mass-produced, whether in the form of New Yorker covers, posters that are printed up and distributed throughout the neighborhood, tattoos that are inscripted on body parts, graphic novels (besides Illuminated Poems, he’s published Flood! A Novel in Pictures and Blood Song: A Silent Ballad), CD covers, or guerrilla-style public art. When Drooker visited the Gaza Strip in 2004, he helped several teenagers from the village of Beit Hanoun paint a giant orange tree on a wall of their youth center. (The Israeli army had already bulldozed every last citrus tree in the area, Drooker wrote in an article for Counterpunch, submitted from an Internet cafe in the West Bank.) He says that while most gallery painters focus on form, his work tries to emphasize substantive content. “I like the image to be very clear, and very concrete,” he explained. “So that it’s about something.”

Drooker’s work is highly accessible, but also can inspire many different narratives — most of them beginning or ending in New York City. In Flood, the principle character — a lonely, alienated, artistic bachelor-type — wanders through a world of tenements, seedy bars, and subway tunnels that turn into a kind of Inferno but also become an extension of the character’s emotional life. The woman in Blood Song rafts all the way from a remote island to New York harbor, after her village is raided by the military. The perils of the city are sublimated in the landscape: giant, oppressive high-rises, cranes, smokestacks, policemen with truncheons. She falls for a saxophone player who offers her canned sardines and cheap wine, and makes love to him on the roof.

That’s a little detail dredged up from Drooker’s past. As a teenager in New York City, he was obliged to share a room with a younger brother who was constantly trying to kick his ass. Rooftops were the only place he could find solitude — and a good view of the skyline.