By Ernesto Aguilar

The Political Media Review

The Sixties presented social movements with some of recent history’s most spectacular schisms, many of which continue to be debated. Assimilation versus revolutionary nationalism versus cultural nationalism; and Old Left aesthetics versus New Left rejection of convention were among them. But none so clearly defined the troubles of that period like the verbal and other skirmishes over militancy.

Pacifism, the use of political violence and the peculiar merging of the two that came to be called self-defense were prominent fixtures of the Vietnam War era. The integrationist sit-ins contrasted with the incendiary solidarity acts of groups like the Weather Underground, which were at times motivated by those same sit-ins as well as the fiery deeds and iconography of the Black Power movement, which itself clashed at points with the mainstream civil rights movement in how each saw the way forward.

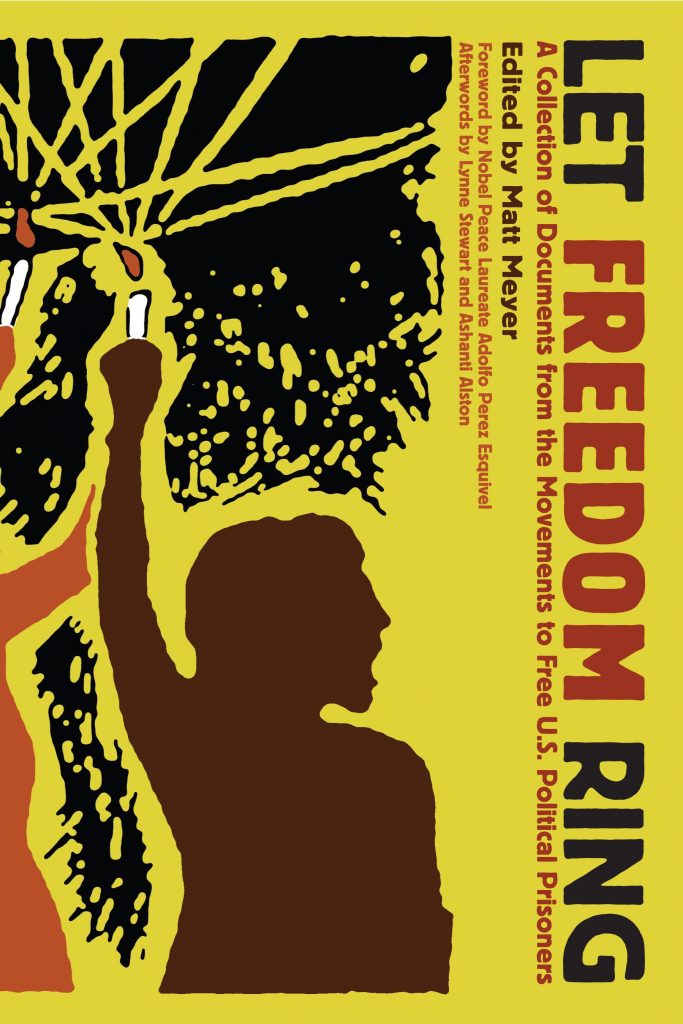

Though it isn’t about those debates, Let Freedom Ring: A Collection of Documents from the Movements to Free U.S. Political Prisoners cannot be divorced from such either.

The massive tome, spanning over 800 pages, endeavors to tell the story of political organizing primarily from the aforementioned period, along with the narratives of individuals incarcerated for activities in alliance with same. The definition of ‘political prisoner’ is most assuredly to be contentious, for in this reading, such encompasses individuals who have taken up political violence as a means to an end. Such a designation, to hear groups like Amnesty International tell it, obscures non-Western activists’ tribulations and the spirit of political resistance. Or does it? Meyer makes a persuasive case for consideration.

Let Freedom Ring brings together scores of previously released documents, featuring former combatants from a constellation of North American organizations including the Black Liberation Army, Weather Underground and more. Many of these writings would have otherwise been lost, and the service Meyer does in capturing a critical though largely unknown call to free those imprisoned for actions associated with political demands in the United States is bold.

Few areas in the realm of such trends are left unaddressed. Race, history, public policy and revolutionary arts are among the themes writers cut into. Meyer should also be applauded for avoiding old-school divisions around political orientation; Earth Liberation Front sabotage, for example, is discussed with the same level of seriousness Puerto Rican liberation campaigns are, and each is presented as part of a larger vision for freedom. Gender and sexism are also plumbed, though more might have been offered. Consider books like Personal Politics: The Roots of Women’s Liberation in the Civil Rights Movement & the New Left by Sara M. Evans to supplement some of Let Freedom Ring’s offerings.

Key business for those interested in the ideas of Let Freedom Ring is how political prisoner movements cross paths with aspirations for criminal justice reform. Jails and poverty impact economically disadvantaged people and communities of color in fathomless ways. Yet, for the commitment former Black Panther Party members and others went to prison in hopes of seeing such disparities end, little progress has been made in linking their hopes and those of people caught up in the prison-industrial complex. Meyer serves to give hope such a connection is possible, and Let Freedom Ring is a great start for organizers seeking not only context but inspiration.