From Prison Photography

“These analyses [of the prison system] – coupled with what I had seen firsthand – made sense, steering me to work towards the dismantling, rather than the reform, of the prison system. Resistance Behind Bars should not be mistaken for a call for more humane or ‘gender responsive’ prisons.”

This is the second in a three part mini-series entitled Women Behind Bars, casting an eye over the work of writers and artists dealing with women’s struggle within the US prison system. The first installment featured journalist Silja Talvi’s work. Today we look at the activism of Vikki Law.

Speaking

“How many people know about the Attica prison riots?” asked Vikki Law. The majority of the audience raised hands. “How many of you have heard of the August Rebellion?” she then asked. No response. Point made.

The August Rebellion was staged in 1974 by women imprisoned at New York’s maximum-security prison at Bedford Hills. Protesting the brutal beating of a fellow prisoner, the women fought off guards, holding seven of them hostage, and took over sections of the prison.

Writing

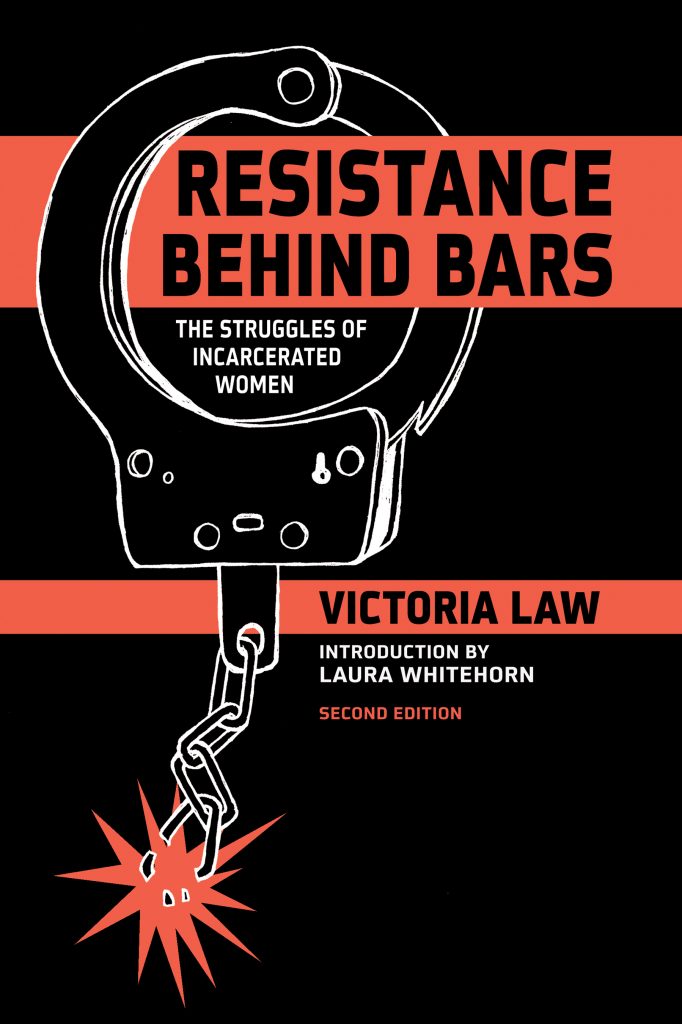

Vikki Law wrote Resistance Behind Bars to counter the historical erasure of women’s prison resistance. The book challenges the reader to question why these instances and efforts have been ignored and why many assume that women do not organize to demand change. It fills the gap in the existing literature, which has focused mostly on the causes, conditions and effects of female imprisonment.

Law has worn many hats in the anti-prison movement. In 1996, she helped start Books Through Bars-New York City, a group that sends free books to prisoners nationwide. In 2000, she began concentrating on the needs and actions of women in prison, drawing attention to their issues by writing articles and giving public presentations. Since 2002, she has worked with women incarcerated nationwide to produce Tenacious: Art and Writings from Women in Prison and has facilitated having incarcerated women’s writings published in larger publications, such as Clamor magazine, the website “Women and Prison: A Site for Resistance” and the upcoming anthology Interrupted Lives.

Similar to Talvi’s work, her writing is uninfected with academese. Law’s focus is the self-organised activities of women prisoners such as forming peer education groups, clandestinely organizing ways for children to visit mothers in distant prisons and raising public awareness about their conditions.

Law will criticise writing that she deems unhelpful and misleading. For example she refutes author Virginia High Brislin’s work which stated “women inmates themselves have called very little attention to their situations,” and “are hardly ever involved in violent encounters with officials (i.e. riots), nor do they initiate litigation as often as do males in prison.”

Law urges us to acknowledge the existing patriarchy of society. The term feminism has become co-opted by predominantly white and privileged classes. The actions that would have previously fallen under the purview of feminism continue in pockets and without a top-down label. She states:

Once such case would be that is described below. Law takes the details from a letter written by the victim.

In the case of Barrilee Bannister, sentenced under Oregon’s mandatory sentencing law, she and seventy-eight other women were sent to a privatized, all-male prison in Arizona run by the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA). The approximately 1300 mile move completely cut the women off from family, friends and others whose outside support could have prevented their abuse.Only weeks after the women’s arrival, some were visited by a captain, who shared marijuana with them. He left it with them and then returned with other officers who announced that they were searching the cell for contraband. They promised that if the women performed a strip tease, they would not search the cell. “Two of the girls started stripping and the rest of us got pulled into it,” Bannister recalled. “From that day on, the officers would bring marijuana in, or other stuff we were not suppose[d] to have, and the prisoners would perform [strip] dances.” From there, the guards became more aggressive, raping several of the women. Bannister reported that she was not given food for four days until she agreed to perform oral sex on a guard. (Source)

Private prisons will forever provide opportunities for gross abuse of human rights, but this is obvious and a discussion for another time. Still, on this evidence, Law has a long road of resistance and a lot of public education to provide. I wish her well.

Photography

Law’s commitments don’t stop with the pen. She also wields a camera and has contributed significantly to the activist-photography community of NYC.

ABC No Rio through a 6-year-old’s Holga, 2006

In 1997, she organized a group of activist photographers to transform one of No Rio’s upstairs tenement apartments into a black-and-white photo darkroom for community use. Since then, she has remained actively involved in coordinating (and sometimes co-teaching) free photography classes for neighborhood youth. In addition, she has participated in and curated numerous exhibitions at No Rio’s gallery, many with themes addressing social and political issues such as incarceration, grassroots efforts to rebuild New Orleans, Zapatista organizing, police brutality and squatting.

Every Halloween, Law also moonlights as a portraitist for ABC No Rio’s free haunted house for kids. As she explains, “Over 400 kids from the neighborhood show up to shriek and scream their way through the first floor and backyard. Tipping my hat to Tom Warren’s “Portrait Studio” in the 1980s, I set up a portrait area to document some of the kids and their costumes.”

Below is Prison Photography’s favourite.

Please read Vikki’s extended resume. Check out Vikki’s Flickr photostream. For a list of resources from The Action Committee for Women in Prison click here.