By Ron Jacobs

CounterPunch

January 6th, 2017

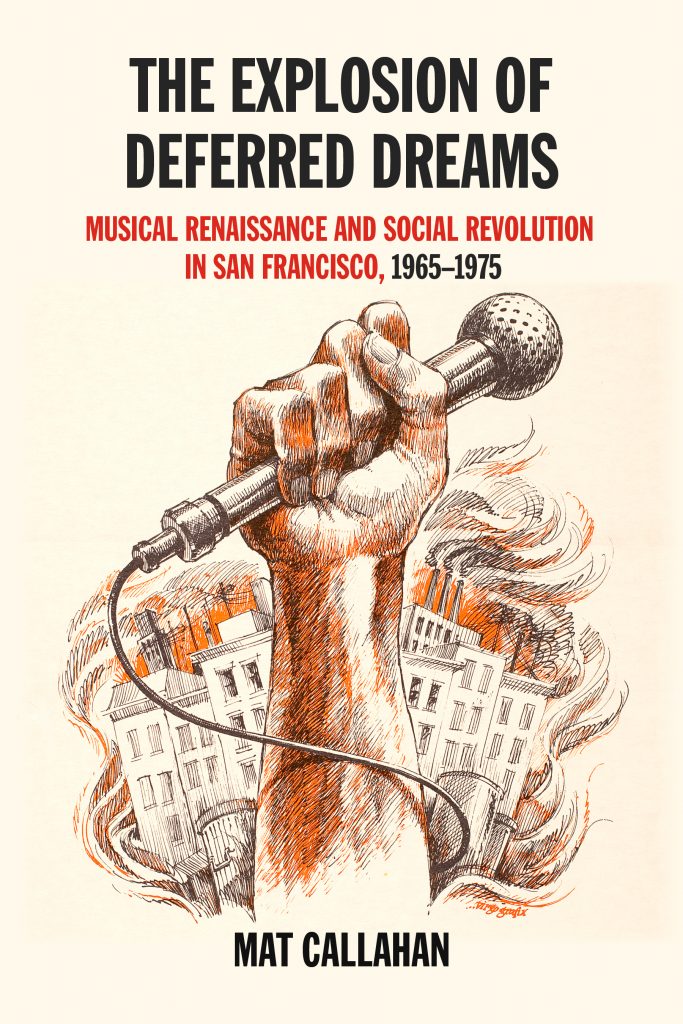

Mat Callahan’s newest book, titled The Explosion of Deferred Dreams: Musical Renaissance and Social Revolution in San Francisco, 1965-1975 is an impressive and exceptional work. Although the meaning of rock music and the counterculture is an oft-explored subject, Callahan brings a new and different perspective to the conversation. One thing in particular that makes this book unique is not necessarily its investigation of rock music and politics, but its definition of the music itself as revolutionary, not just its lyrics. In other words, it was the rock sound, especially that played by so-called psychedelic rock musicians from the San Francisco Bay Area, that were often more important than the lyrics. Why? Because those sounds liberated the body and the mind—the entire being. This liberation threatened the existing social order as much as any revolutionary lyrics or protests might. At the same time, they existed within limits that could eventually be made something other than revolutionary. This latter truth is part of any discussion of the meaning of the 1960s; naturally Callahan takes it on, too.

In 1975, I saw Callahan perform with the 1970s folk-rock duo Prairie Fire (Prairie Fire became a punk band later in the decade and worked with the Revolutionary Communist Party.) Afterwards he and his fellow band member led a discussion on the meaning of rock music in the revolutionary spirit of the mid-1970s. I recall the discussion as being a good one, although there were occasional short silences while the audience, which was made up of politicos and counterculture freaks, attempted to reconcile the contradictions between Bob Dylan’s support for George Jackson and his blatantly apolitical music of the early 1970s. What strikes me most about this memory is how much music actually mattered in the lives of both political and cultural revolutionaries then. This is the spirit this book is written. Indeed, Callahan draws on both his radical and musical pasts in The Explosion of Deferred Dreams.

From the Fillmore and Avalon dancehalls to the KMPX and KSAN radio waves, this grassroots revolution in music was created by the people in the streets and houses, not by producers and corporations. However, given that this occurred in the world’s biggest and most powerful capitalist nation, it would not stand. Then again, perhaps it would not have stood in a lesser outpost of profiteering, either. The battle for the music and its genuine soul is another crucial element of this text, as well. Callahan discusses this throughout the book from a variety of angles—musician, promoters, media, audience and the record companies. In his discussions, he saves a special venom for the promoter Bill Graham and the Rolling Stone newspaper founded by the nowadays media mogul Jann Wenner. By pointing out Graham’s intense pursuit of profits in spite of opposition from a more egalitarian community, he explains how Graham’s almost innate understanding of the business (despite his lack of experience) both destroyed the ethos of community while simultaneously saving the financial asses of certain groups like the Grateful Dead. In discussing Rolling Stone’s access to musicians, he also points out how the magazine became a shill for the industry, which ultimately helped force its competition out of business.

This book takes us deep into the nexus where art and politics collide and collude; specifically, the nexus where the music of the San Francisco Bay Area colluded to help inspire and inform a cultural revolution that changed minds and social realities. Written in the context of revolutionary culture—with Mao, Marcuse, Marx and Fanon as informants—The Explosion of Deferred Dreams brings Simone De Beauvoir, the Black Panthers, La Raza and the Students for a Democratic Society into the discussion, as well. The result is a radical left critique of culture under monopoly capitalism and a fun ride through the streets, parks and dance halls of 1960s-1970s San Francisco. The reader becomes an observer of community meetings and community squabbles over art and profit. They are also presented with an argument that describes the racial and ethnic diversity of the Bay Area’s counterculture scenes. This latter element is often ignored by most writers and, to be fair, the reality is that the counterculture was mostly a white-skinned phenomenon. However, if there was one geographical region where this was less so, it was the Bay Area. Rock bands did benefits for the Black Panthers and striking farmworkers and the people in the streets banded together across color lines to defend their culture, their public and private spaces, and the revolution against the cops, the mainstream media and establishment politicians.

Unfortunately, the power of money won out. The rock music audience became segmented along multiple lines, including race and gender; concerts were rarely ever free; and radical politics were repressed and removed. Yet, the suggestion of that liberation one feels when they hear certain songs—the ones that make you shake your hips or pump your fist—remains. It will never go away and one hopes it will continue to be discovered anew. Mat Callahan helps make sense of why this is so.