By Michael Fox

From NACLA

By Alexis Stoumbelis, Lisa Fuller and Michael Fox

The

day before President Barack Obama arrived in San Salvador on March 21,

thousands of union members and campesinos marched to the U.S. Embassy.

Over the loudspeaker an organizer proclaimed, “The global economic

crisis, climate change, narcotrafficking, insecurity and the food crisis

have their origin in the economic model imposed on our people by the

great world powers, primarily the United States.” Outside of President

Obama’s press conference the following day, hundreds of Salvadorans

carried photos of family members who had been killed and disappeared

during El Salvador’s civil war, in which U.S.-backed government forces

brutally repressed the leftist Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación

Nacional (FMLN). Marching alongside them, Hondurans bared crosses on

their backs in memory of the hundreds of activists who have been killed

since the June 2009 coup against President Manuel Zelaya.

Days

before, in Chile, demonstrators denounced the proposed nuclear energy

agreements and called on the United States to acknowledge its role in

the 1973 CIA-backed coup against then-president Salvador Allende.

Mobilizations in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil forced President Obama’s press

conference with Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff indoors, as

protesters chanted, “Go home, Obama . . . the petroleum is ours.”

Throughout the hemisphere, people waited to hear whether President Obama

would demonstrate the new era of “mutual interest and mutual respect”

with Latin America that he had promised during his campaign. What they

heard was mostly “más de lo mismo” (more of the same), dressed up in a language of “partnership” and cooperation.

Even before President Obama had embarked on his five-day trip to Latin America, he made clear that the primary motivation for the trip

was to increase U.S. exports to the region and, in doing so, create new

U.S. jobs. His goal, in this “fiercely competitive world,” was to

ensure that Latin American countries would import most of their goods

from the United States, not from China, the European Union, or other

Latin American countries. This was especially apparent during Obama’s

first visit to Latin America’s largest economy, Brazil, where China has

just overtaken the United States as the number one trading partner.

Brazil, with an economic growth rate of 7.5 percent per year, is also

the world leader in ethanol production, and home to the recently

discovered deep-water oil reserves, known as Pre-Sal, estimated by some to be larger than the combined reserves of the United States, Canada and Mexico.

While

culturally significant—the first African-American U.S. president

visiting Brazil’s first female president—Obama’s visit was overshadowed

by his authorization of the Libya bombing while in Brazil. Meanwhile, as

one columnist for the Brazilian newspaper, Folha de São Paulo pointed out,

Obama lacked “deliverables” or “concrete results.” Brazilians were

disappointed that Obama failed to announce support for their country’s

bid for a permanent seat on the UN Security Council. For all of his

rhetoric of increasing trade, Obama didn’t offer any solutions to the

54-cent per gallon import tax the United States levies on Brazilian

ethanol. Obama did, however, offer billion-dollar funds to help

Brazilian businesses purchase U.S. products and to support the Brazilian

development of their off-shore oil rigs, promising that the United

States wants to become “one of [their] best customers.”

In

Chile, Obama and Chilean President Sebastián Piñera initiated talks on

launching Chile’s nuclear power program, a move that many consider

reckless amidst the ongoing disaster at Japan’s Fukushima nuclear plant,

and Chile’s earthquake-prone history. Like the rest of the trip, Obama’s speech

to Latin America from Chile’s La Moneda Presidential Palace embraced

hemispheric cooperation, while lacking substance. He quoted from Chilean

poet, Pablo Neruda, applauded the heroic Chilean miners, and reminded

listeners that “Todos somos Americanos” (We are all American).

He also praised Chile on its leadership in transitioning “from

dictatorship to democracy”, but failed to apologize for the U.S. support

of the seventeen-year-long military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet.

While

Obama applauded Brazil’s biofuels and Chile’s geothermal energy

programs as examples of “alternative energy,” his support for off-shore

rigs is more of the status quo; meanwhile, opposition to extractive

industries from grassroots social movements and indigenous peoples

continues to rise throughout the Americas, as evidenced during the April

2010 World People’s Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of

Mother Earth in Bolivia. It’s worth noting that Brazil’s ethanol program

has come under fire from indigenous communities, as have biofuel

megaprojects in Mexico, Guatemala and elsewhere.

Obama

arrived in El Salvador on Monday, March 21, where the gulf between the

reality and the rhetoric of a “new era” was perhaps most palpable and

painful. He made a highly celebrated visit to the tomb of revered martyr

Monseñor Oscar Romero, who was murdered in 1980 by members of the

Salvadoran armed forces who were trained at the School of the Americas.

However, Obama also announced $200 million for a security initiative to

combat narcotrafficking in Central America. Many fear the move could

increase human rights violations, as in Mexico,

where over 36,000 people have been killed since 2006 in the “War on

Drugs.” Before the trip, William Brownfield, Assistant Secretary for the

Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs and

former U.S. Ambassador to Colombia, announced the plan to transform

Central America into a “security corridor”

between Colombia and Mexico, despite the fact that the Merida

Initiative and Plan Colombia have increased the profitability of the

drug trade and driven cartels into Central America.

Fortunately,

Salvadoran President Mauricio Funes’s joint statements with Obama

reflected a significant shift from the “crackdown”-only approach of

Mexico’s Felipe Calderón or Colombia’s Juan Manuel Santos. President

Funes emphasized that state investment in job creation, rehabilitation

and prevention programs was the only way to stem the proliferation of

organized crime and emigration. “We cannot continue offering our

youngsters [only two choices], go to the United States to find

employment … or to fall in the hands of the criminal gangs,” said

Funes. In another welcome change, at least rhetorically, President Obama

said that Central American governments, not the United States, would

design and implement programs for the new Central American Regional

Security Initiative (CARSI).

Sadly,

although Obama agreed with Funes that an economic solution is needed,

the economic policies he promoted were largely a continuation of the

last twenty years of neoliberalism, which has resulted in the majority

of El Salvador’s population living on less than $2 per day. His focus on

fostering foreign investment

as the path to development was especially hard to swallow, as the

Canadian mining corporation Pacific Rim is currently suing El Salvador

for over $100 million in alleged “lost profits.” Pacific Rim is the very

type of foreign investor that Obama hailed as El Salvador’s potential

savior.

As

during his trip to Brazil, Obama’s new economic assistance for El

Salvador, including the yet-to-be-defined BRIDGE (Building Remittance

Investment for Development Growth and Entrepreneurship) and Partnership

for Growth programs seem intended to continue a vicious cycle of

exploitation and dependence, cementing U.S. economic access to countries

that, quite frankly, are getting better offers elsewhere, including

China and other Latin American nations.

Perhaps

President Obama’s praise for President Funes’s “pragmatism” was meant

to assure him that support would be provided as long as corporate

interests remained in the driver’s seat. As recently as the June 2009

coup d’etat in Honduras, the Obama administration showed that it

wouldn’t defend Central American presidents who strayed too far to the

left, for example, by joining the ALBA, the Bolivarian Alternative for

the Americas. FMLN-governed municipalities in El Salvador have been

participating in ALBA initiatives with Venezuela for several years, and

some co-operation with Cuba has now reached the national level through

the FMLN-led Ministries of Health and Education. But maintaining U.S.

support is a huge priority for any Salvadoran president, as nearly 2.5

million Salvadorans—roughly 30 percent of the population—live in the

United States.

Ultimately, President Obama’s meeting with El Salvador’s first progressive president is significant not only for El Salvador, but also for the hemisphere. Movements that continue to resist the neoliberal agenda have shifted the terrain, forcing the United States to contend with some of the very political forces, like the FMLN, that they spent hundreds of millions of dollars trying to defeat in the 1980s. Social movements, progressive presidents and global economic changes too, have pushed President Obama to talk about “common prosperity,” even if real cooperation is still a long way off.

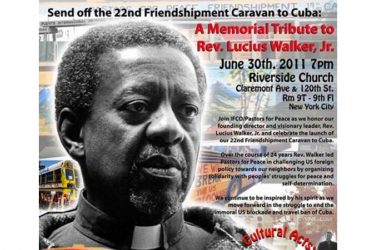

Alexis Stoumbelis and Lisa Fuller work with the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador in Washington, DC (CISPES). Michael Fox is Associate Editor of NACLA. His work can be read at his blog.