By Steven Tufts

Antipode

April 15th, 2019

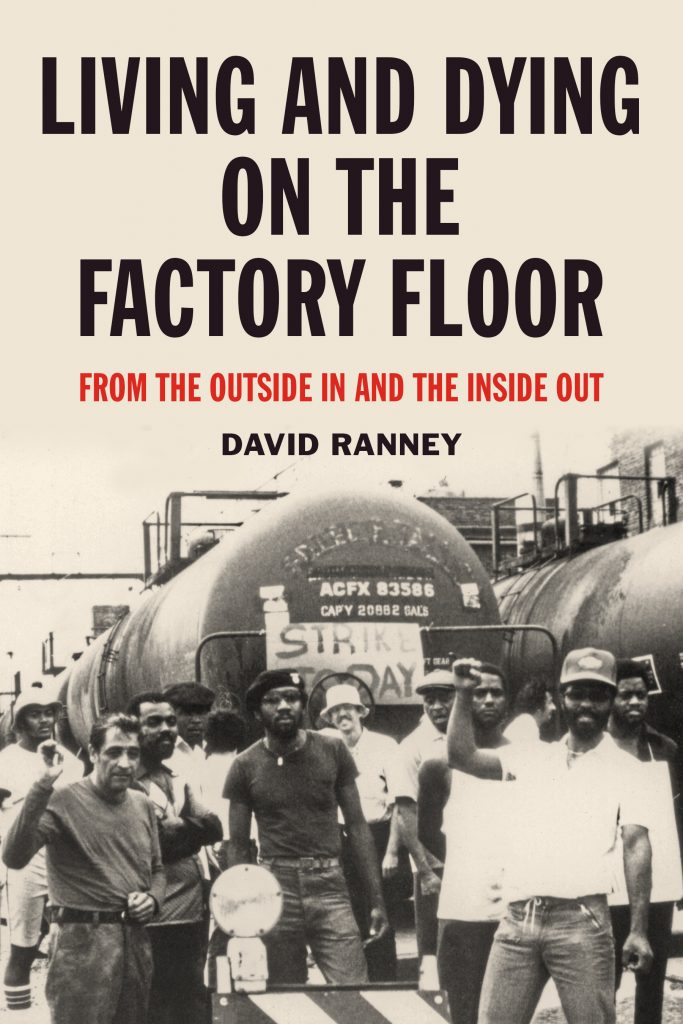

David

Ranney, Living and Dying on the Factory Floor: From the Outside In and

the Inside Out,Oakland: PM Press, 2019. ISBN: 978-1-62963-639-9 (paper)

The

pipeline from activism to academia is well established. Many of the New

Left that took up full-time academic positions in the 1970s and 1980s

transitioned quite well from the workplace, the union office, the

street, or even the jail cell to the respectability of the lecture hall.

Most continued activism within the university. As this generation ages,

there are moments of reflectionon past political work and the lessons

learned.

David Ranney’s book is both within and beyond this genre. Living and Dying on the Factory Floor could be considered a didactic memoir, but that would too easily dismiss the pages that read like a novel and discount many other passages with cutting analysis. The short book is an account of Ranney’s life from 1976 to 1982 when he worked in a number of factory jobs in southeast Chicago and northwest Indiana. The author was an active member of several revolutionary organizations who at the time sent members into factories to engage workers independently of unions. One such group that shared this practice was the Sojourner Truth Organization (STO) which greatly influenced Ranney’s politics. The organization named after the mid-19th century escaped slave and activist operated throughout the US Midwest in the 1970sand early 1980s. STO was not only skeptical of any transformative potential of unions and Sovietstate capitalism, but also situated white supremacy at the forefront of analysis and action.

Ranney captures this period with detailed narratives of life at work in different factory settings and at a Workers’ Rights Center. From his falsified work experience on job applications to the exhausting heat, stench, noise, and pollution on the shop floor, his account brings the workplaces to life. The author takes us on a journey from his first job re-servicing centrifuges to a box factory, shortening production, rail freight car assembly, steel fabrication, paper cupproduction, and steel mill equipment manufacturing. Each workplace reveals challenges from unsafe work and injuries to rampant racism and corrupt strike-breaking unions.

The experiences are recounted with humor and melancholy. Again, it reads like a novel with dialogue among workers and bosses establishing a number of unforgettable characters. An alcoholic who emerges as a leader during a strike and racist white men concerned primarily with their position in a racial hierarchy haunt the reader as well as the author. The stories of strikes, union drives, and immigrant workers escaping raids by La Migra all unfold with suspense and passion.

Important themes run through the accounts of the factory floor that Ranney develops in concluding reflective chapters. First, the drudgery of factory work in the narration in no way romanticizes the manufacturing sector. From the filth of the workplaces to the dangers of the work itself (including when the author badly burnt his face), the manufacturing labor process is seen for what it really was like. Ranney also sheds light on what the manufacturing sector was becoming as lines were automated and jobs outsourced. “Bringing back middle-class jobs” via manufacturing remains a contradiction (p.119). As the author notes in this and his other work (Ranney 2003, 2014) the outsourcing and deindustrialization which have destroyed communities are, in part, responses by capital to the demands of blue-collar workers in the first place.

Second, Ranney centers the racial division of labor as “both the keystone and mortar of the US factory system” (p.123). Here he echoes the work of C.L.R. James and the political writings of Noel Ignatin and Ted Allen (2011) as white-supremacy must never be “side-stepped” in order to focus on a false white masculine class-unity. Similarly, the issue of immigration which divides legal and illegal workers also needs to be viewed as a mechanism of class domination.

Third, Ranney reflects on the relationship between Left intellectuals and workers. He situates himself at a midpoint in the insider/outsider binary as someone having “dual status” with the privileges that come with whiteness and education. Cleverly, he turns to the different experiences and backgrounds of the workers he stood beside as complex “social individuals” (in the Marxist sense) with just as many contradictions. Ranney is optimistic that these differences can be transcended as unity is formed in moments of materialist struggle.

As much as I enjoyed this well-written book, I was left with a sense of frustration. In many post-industrial workplaces, the same issues portrayed by Ranney persist today. Fragmentedworkplaces with racial divisions of labor have not disappeared. Anti-black racism and labor market exclusion and anti-immigrant policies seem as prevalent as they were 35 years ago. And while manufacturing employment has declined in some economies, there are still large workplaces that could be targeted for mass organization, if an organized Left of any significance actually existed.

There is also a slight incompleteness in the work. Perhaps, I just wanted more from a project that is clearly designed to focus on a specific moment. Yet, I wanted to know more about the experience. Ranney is careful to avoid the “white savior” trope that creeps into many “outsider” organizing stories. He is clear that the STO position was to encourage and support resistance but not agitate as they did not have the capacity to support workers put in jeopardy. Was this really the case? In some of the events that unfold such as the strike at the shortening factory, he does appear to be in a leadership role and a threat to corrupt union leadership.

Ranney comes clean with his own limited understandings of the racist mechanisms of the workplace at the time. For example, only after reflection and talking with workers did he realize racist tests were used to exclude workers from the jobs he had. He does, however, come short of placing himself within these racial structures. In some accounts he ignores racist statements by co-workers, while directly confronting statements (and even Nazis) in others. What explains these different approaches at different times, and what are the contradictions of fighting in a racially divided workplace when your own presence in the hierarchy reproduces it? Similarly, more could be said about the masculinity and gender relations in these largely male workplaces. Here, is where I was left wanting for more reflection.

There is also the question of a tenured professor taking paid factory work. In the preface, Ranney speaks about his choice to leave academia and his tenured position at the University of Iowa in 1973. In his case, the pipeline from activism to academia was anything but linear as it went from activism to academia to activism to academia again. In today’s job market such a choice seems unimaginable given that landing a tenure stream position is almost like winning a lottery. The allure of political organizing in the factory was, however, strong enough to pull the author from his “comfortable perch”. In one particular history of the STO, Ranney has gone on the record that he (and others) were so convinced of the importance of organizing at the point of production that a split occurred in the organization when the leadership shifted to political organizing within the “white Left” (see Staudenmaier 2012: 144). If we accept this account, it raises some serious questions about the relationship between Left activism and workplace organizing. How many Left academics would leave secure employment to get a job at Walmart or Amazon? Is it a viable or preferable strategy over the long-term? After all, even Ranney himself returned to academia after dedicating a decade to organizing in factories.

Living and Dying will appeal to a number of audiences. Those with interests in labor studies and organizing, political formations emerging out of the New Left, and autobiography as research method should all read it. But anyone with a sense of humanity and social justice who has ever worked in a factory will eagerly turn the pages. For this reason alone, I really do hope the book travels beyond academia and makes it to the factory floor.

References

Ignatin N and Allen T W (2011 [1967]) The White Blindspot Documents. In C Davidson (ed) Revolutionary Youth and the New Working Class: The Praxis Papers, the Port Authority Statement, the RYM Documents, and Other Lost Writings of SDS (pp148-181). Pittsburgh: Changemaker

Ranney D (2003) Global Decisions, Local Collisions: Urban Life in the New World Order. Philadelphia: Temple University Press

Ranney D (2014) New World Disorder: The Decline of US Power. North Charleston: CreateSpace

Staudenmaier M (2012) Truth and Revolution: A History of the Sojourner Truth Organization, 1969-1986. Oakland: AK Press