By David Rosen

New York Journal of Books

April, 2019

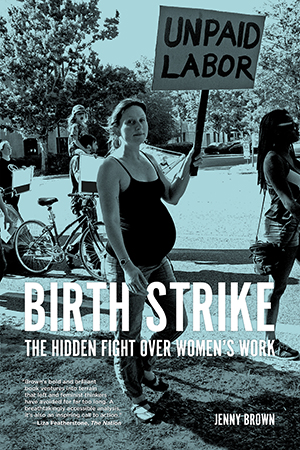

Is a baby a commodity? Is pregnancy and childbirth work? Is raising a

child a job? These are among the provocative questions that inform Jenny

Brown’s study, Birth Strike: The Hidden Fight over Women’s Work.

Brown

is a feminist without sentiment, a Marxist without humanism. In this

well-researched work, the author seeks to strip away all sentiment from

people’s—especially women’s—understanding of the economic role of the

domestic services women perform. She sees such service as a form of

undervalued and unpaid labor. These services include pregnancy and

childbirth, rearing a child and all the domestic chores required to

maintain a household, and taking care of the elderly and infirmed. As

the old saying goes, a woman’s work is never done.

This

argument is compounded by the book’s underlying thesis, the “baby bust.”

She reminds readers that during the post WW-II era of the “American

Dream” “the wages of one full-time male breadwinner” was enough to

support a wife and kids, but now “two breadwinners are necessary to

support a family.” In the face of this historic change, Brown argues,

“women are deciding to have fewer children.”

Brown identifies

two significant consequences of this development. First, corporate and

political “elites are foretelling economic doom if women don’t step up

reproduction.” She quotes a conservative writer who asserts, “declining

birth rates constitute a problem for the survival and security of

nations . . . in the broadest existential sense of national security.”

Second, she stresses that the elites are using the power of the state,

including the Supreme Court, to restrict a woman’s right to an abortion

and limit contraception and birth control information (especially for

young girls). The outcome of these developments is a decline in

fertility rate.

The decline in the fertility rate is occurring

at a time when life expectancy has significantly increased. Brown notes

that in 1900, U.S. life expectancy was only 47 years and by 2018 it has

jumped to 79 years. Compounding this picture, the Guttmacher Institute

reports that nearly two-thirds (62%) of all women of reproductive age

use a contraceptive and nearly all women aged 15–44 who have had sexual

intercourse used at least one contraceptive method. Equally significant,

between 1991 and 2014, the teen birthrate fell by nearly 40 percent, to

24.2 births per 1,000 females from 61.8 births, due to sex ed and use

of contraceptives.

Embracing a traditional Marxist analysis,

Brown argues that women are part of the “reserved army of labor.” She

repeatedly reminds readers that conservative policymakers promote

anti-abortion and anti-birth-control policies in order to promote an

increase in the birth rate. The increase would help foster cheap labor.

She details her critique through extensive discussions of birth rates

and women’s work in terms of immigration, race, and labor practices.

She

also makes clear that the U.S. is not alone facing the

“below-replacement birth rate”; other countries facing a similar decline

include China, Japan, Germany, and the UK. She insists that “the fight

over the birth rate is mainly aimed at extracting another type of cheap

labor: the labor of bearing and rearing children.”

Amidst her

rigorous analysis, one small question comes up. In a chapter reviewing

the history of the debate over the birth rate, she notes that in the

early 20th century, leading radical socialists like Rosa Luxemburg,

Clara Zetkin, and V. I. Lenin argued against what they believed was the

moderate socialist position promoting the “birth strike” to contest

capitalism.

While apparently intellectually and politically

identifying more with radicals, Brown argues: “A birthrate slowdown or

strike, accompanied by feminist organizing and protest, might pressure

the power structure to provide better working conditions for

reproductive work, but the problem isn’t too many children to being

with.”

Drawing on the experiences of other advanced Western

society, Brown recommends that the U.S. needs to introduce a national

health care program, free abortion on-demand and birth-control,

universal free childcare (and eldercare), parental leave for all, and a

shorter work week. It’s unlikely that a birthrate strike will do much to

realize these important goals.

David Rosen’s most recent book is Sex, Sin & Subversion: The Transformation of 1950s New York’s Forbidden into America’s New Normal. His articles and book reviews have appeared in such diverse venues as Salon, Black Star News, Brooklyn Rails, Huffington Post, CounterPunch, Sexuality and Culture, The Hollywood Reporter, and others.