By Simon Davis-Cohen

In These Times

March 15th, 2016

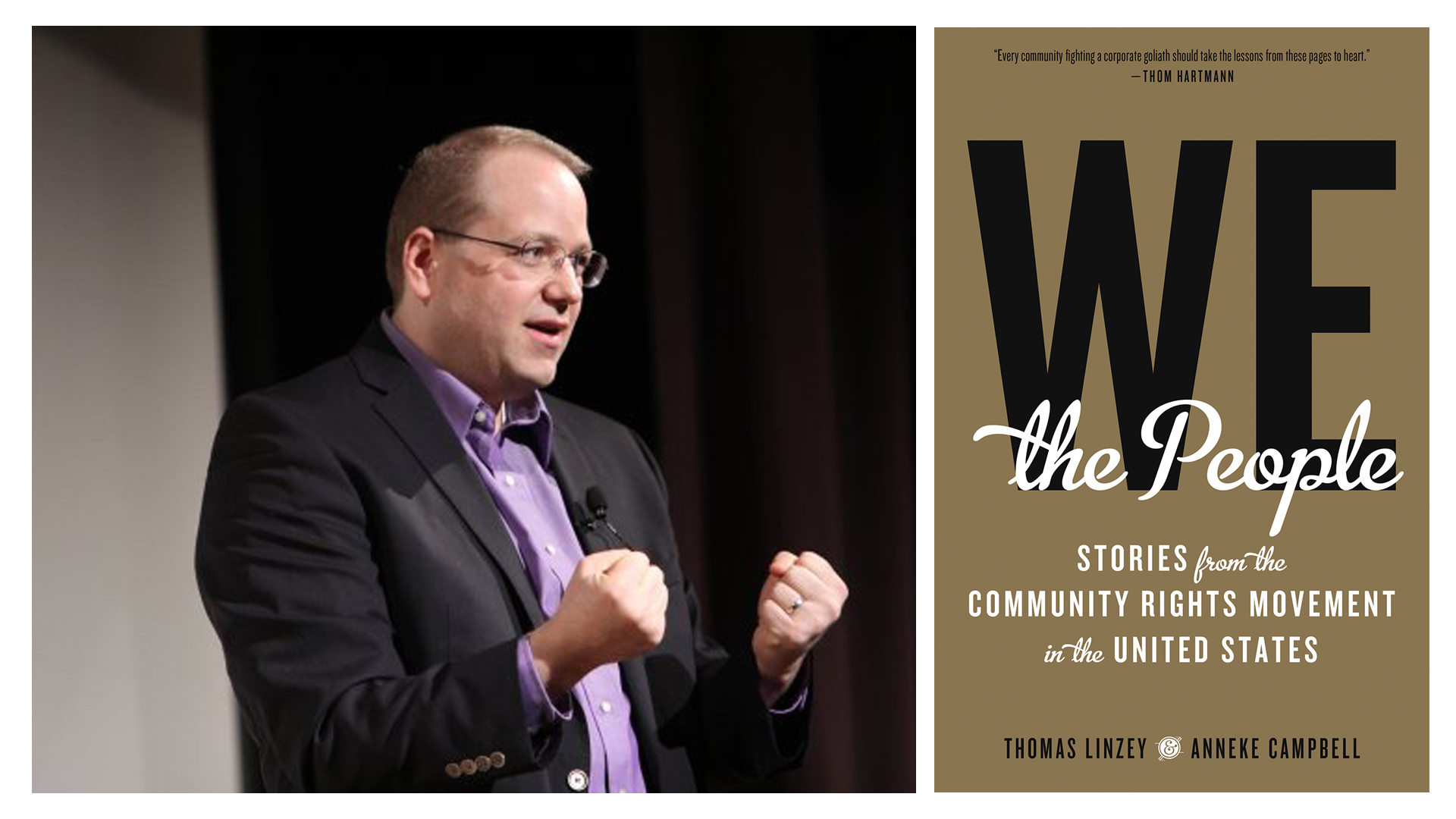

Thomas Linzey is the cofounder and executive director of the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF). (celdf.org)

Editor’s Note: Thomas Linzey is no stranger to Rural America readers. His Community Rights Papers are a staple on the site. In fact, his essay, “The Spirit of 1773 and the Right to Local Self-Government,” was the very first story this project published one year ago. In the months since, we’ve featured seven other of his essays, but until now we have never interviewed the man behind America’s “community rights movement.”

For 20 years, the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF) has been taking a stand against the long-held—though rarely discussed—assumption that corporations in the United States have the power to override a community when the locality passes a law that compromises profitability.

To date, the Pennsylvania-based, non-profit law firm has advised almost 200 municipalities in 10 states in drafting and defending “Community Bills of Rights.” These documents are often adopted to stop harmful corporate projects by elevating local governments’ authority above anti-democratic state preemption and the legal protections corporations enjoy as “persons” under the U.S. Constitution (and international trade agreements).

CELDF has spearheaded the introduction of legally enforceable rights for ecosystems; over three dozen of the communities they work with have enshrined such “rights of nature” into local law. CELDF has also aided the special Ecuadorian Constituent Assembly in its successful effort to include enforceable rights of nature in the country’s 2008 constitution. Most recently in 2016, the Green Party of England & Wales worked with CELDF to include rights of nature in its official party platform.

People are taking notice. The Independent Petroleum Association of New Mexico warned against CELDF’s community rights organizing, calling it, “the beginning of a social movement that is greater than just the oil and gas industry, it is a potential game changer for all of corporate America.” In Benton, Ore., the county attorney recently suggested those petitioning for a Community Bills of Rights to ban GMO agriculture be labeled “domestic terrorists.”

Liberal activists who work to appeal regulatory permits and support direct action also criticize CELDF for abandoning the regulatory system and challenging the logic of direct action. The concept of local control is often criticized as well. Yet in places where CELDF has proposed state constitutional change, we see the movement advocating not for total local control but rather for communities’ authority to raise and improve state standards.

I sat down with CELDF executive director and co-founder Thomas Linzey to discuss some of the ideas, differences of opinion and miscommunications surrounding the group’s work.

Self-governance, collective direct action and not giving up when your community gets sued

Rural America: CELDF’s theory of change can be summarized as follows: Local law-making can be used as an ends to stop activities that harm people’s lives, and as a means to organize a broader grassroots movement to drive state and eventually federal constitutional change. The case for such constitutional change is embodied in each local laws’ elevation of community self-determination (for both human and natural communities) above the power of corporations and other levels of government to override core aspects of local democracy.

CELDF has helped close to 200 U.S. communities pass such laws. Now, in seven states, networks of these local communities are banding together to change their state constitutions. Then, once enough states sign on, the federal social contract can be changed—thus giving birth to both a state and federal constitutional right of local, community self-government that trumps both corporate “rights” and legal doctrines that currently make municipalities completely subordinate to their state.

When I talk to people about CELDF’s approach, some people say they don’t have faith that change can come through a legal system where so many judges and lawyers have been captured by the status quo. What do you think of this critique?

Linzey: It’s not a legal strategy, first of all. While we believe that there may be some judges and courts out there ready to embrace a right of local, community self-government, our communities aren’t betting on it. Eventually, they understand that for this type of change to happen, they’ll have to drive that change into their constitutions and override the courts. After all, it’s the courts that have created many of these doctrines over the past hundred years or so; to turn back to them to undo them would be pretty naive. So, we pursue two tracks—vigorously defending these communities in the courts when they get sued by corporations or their own state; and second, assisting communities to come together to drive local self-government guarantees into constitutional structures.

Rural America: You have said that CELDF’s work is compatible with direct action. Direct action can involve breaking a law to convey a message or trying physically to prevent harm from proceeding—there are endless examples. For example, we can imagine a scenario where, after passing a Community Bill of Rights, citizens might resort to protest in order to stop corporate activities that do not acknowledge or honor the Community Bill of Rights. How do you view direct action?

Linzey: We would argue that the local laws themselves are direct action—that they are collective direct action and civil disobedience, rather than individual direct action. In other words, by their very existence and adoption by the community, they are a repudiation of a structure of law that ordinarily subordinates the community to corporate control. The local laws thus nullify the three primary legal doctrines that create that overarching corporate control, and in the process, they break those laws across the board. So, instead of one person sitting in front of a bulldozer, these local laws mean the entire community is sitting in front of the bulldozer, and using the municipal government as their weapon against corporate power. In addition, many of these local laws now legalize direct action to enforce the laws—prohibiting local law enforcement from arresting individuals for directly enforcing the local laws, for example.

Rural America: If you were to draw a Venn diagram, with direct action and community rights activism representing the two circles, what would you include in the “overlap” portion of the diagram—what do they have in common?

Linzey: Breaking the law frontally, directly and forcibly.

Rural America: What about the “Community Rights” portion—what does Community Rights activism encompass that direct action does not.

Linzey: Traditional direct action involves breaking criminal laws. The community rights activism understands the need to “take back” the law itself—to change the lawmaking platform, so that traditional direct action, if it proceeds, is built on that lawmaking, thus making the direct action not “against the law,” but to “enforce the law.” It places the power of majorities behind civil disobedience, rather than having civil disobedience remain some kind of tool of “protest.” It’s about resetting the default.

Rural America: Lastly, the “direct action” portion—what does direct action activism encompass that community rights activism does not.

Linzey: Community rights activism changes the forum—away from the streets and the jail to challenging the very authority of the corporation to use the system of law. It’s about going upstream to the source, rather than simply accepting that the law will always be used to punish those who stand in the way of endless economic growth. There is a clear distinction. One opposes a law; the other defends a law. Oppositional direct action sends a message about what activists don’t want, whereas defenders of a Community Bill of Rights have first organized around what they want: the values and rights enshrined in their Community Bill of Rights. If community rights activists resort to direct action, their protest embodies a vision.

(Image: wikipedia.org)

Rural America: Civil disobedience means the breaking of the specific law you want to change. But our culture often tells us that it is not the law, but how it is enforced that is the problem. How do you see CELDF’s work as a form of modern civil disobedience?

Linzey: Yes,I think that over the years the phrase civil disobedience has been stripped of most of its meaning in the culture. The corporate culture that we live in has worked very hard to rid us of the very language that prior generations have used to frontally challenge the system. Part of our work is to help people re-discover that right language and history. What makes America great isn’t all of the things that the presidential candidates talk about it, our “greatness” lies with the courage of the Abolitionists, the resoluteness of the farmer/soldiers without shoes at Valley Forge, and the sheer determination of the Suffragists—all men and women outside of traditional power structures who succeeded in changing those structures.

Rural America: Pablo Iglesias, leader of Spain’s new Podemos political party, has written that the country must “confront…the political myopia of those who only feel comfortable as part of a minority.” Activists want to identify at being part of an enlightened minority can stop them from planning what to do with power should they gain a majority in a community, county, region or state. Why is this a particularly good time to think about what to do with power, rather than merely fixating on how to gain power?

Linzey: I think the time is ripe because a lot is becoming very clear—in terms of the loss of community democratic control and the continuing implosion of the planet. I think we’re coming to a point where more and more people are having their minds freed from the constraints of the crap that’s put out by those in control. I think the only majority we feel a part of is sanity; and the belief that when people are able to see through the charade, they end up with a belief system similar to ours—that centralized power, in whatever form, is a bad thing and that the only place real solutions are going to emerge from is our communities.

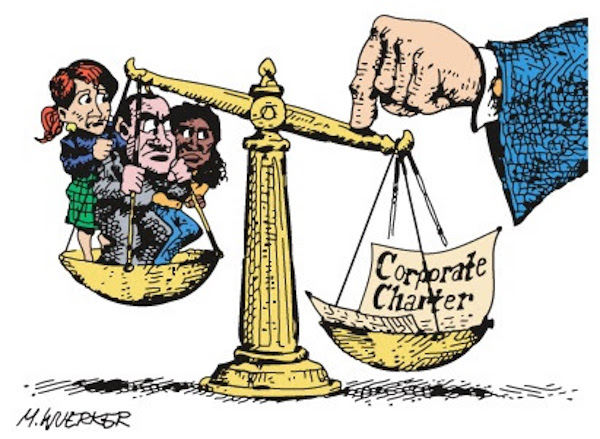

(Image: Matt Wuerker / celdf.org)

Rural America: Any vision must include economic alternatives. Clearly, the community rights movement is a political one but it is not hard to see community rights activism’s compatibility with cooperatives, mutual aide networks, community-owned renewable energy, etc.—movements that engage in and foster economic alternatives. In your view, what is stopping movements for democratic control, like community rights activism, from working more closely with movements that push economic alternatives? And what’s one way they could work more closely?

Linzey: For those economic alternatives to grow, we have to clear the way for them by ridding the system of corporate and governmental power. We also have to get used to what makes us uncomfortable—using our governments to actually promote and mandate those alternatives. Liberals are particularly uncomfortable with, say, a local law that requires that the only agriculture done in a community is organic; or a local law that requires grocery stores to carry 30 percent locally-produced vegetables. Yet the corporate boys have no worries about using the law that way—it’s why they use farm laws, for example, to prohibit neighbors from suing over factory farms. They use government and laws to actually support the type of production that favors them. We have to begin doing the same thing – seeing law and government as a way to fashion the markets that we want. But we haven’t done that over the past 50 years—instead, we keep pretending that the corporate boys will leave us alone to build these alternatives. The problem is that when the alternatives get big and threatening enough, they use their power to shut them down. It’s why we can talk about “alternative” economics all we want, but without dealing with corporate power, it goes nowhere.

Rural America: Increasingly, the labor movement in this country is turning to local law making to do things like raise the minimum wage, establish fair scheduling policies or pass paid sick leave legislation. In response, corporate lobbies, like National Restaurant Association and American Legislative Exchange Council, are pushing preemption bills to remove localities’ power to legislate on these issues. However, the worker movements are not directly targeting preemption itself, though it is clear that preemption is a primary tool used against them. What do you say to this? What would it take for these movements to challenge preemption itself?

Linzey: Community rights activism directly targets preemption, because preemption itself is caused by corporate control over the governmental system. When something becomes a big enough problem, the corporate boys in a particular industry simply use government to shut down local activism around the issue. I haven’t seen any of these movements begin to directly target preemption—the power of preemption—rather, they lobby to stop the preemption from happening. Almost nobody questions the authority of the state or federal government to preempt community lawmaking—the authority itself—it’s just accepted that the federal should be able to trump the state and the state trump the local. But, the operation of that machine is exactly the opposite of democracy—it pulls decision making into hands further away from where the problem is, and into fewer hands.

(Image: Matt Wuerker / celdf.org)

People don’t understand that preemption itself (the state/local relationship, where most preemption occurs) is a purely judicial construct, invented by the courts, and built on the fact that municipalities are deemed to be wholly creatures of the state, for the state to use and abolish as the state sees fit. If that’s the underlying truth, then preemption makes perfect sense.

Rural America: Many people have tracked a modern decline in the power of nation states. As Pablo Iglesias wrote: “The transfer of sovereign power (military, economic, judicial, etc.) from the so-called nation-states to supranational organisms (Troika, IMF, World Bank, NATO, mammoth private corporations credit rating agencies, etc.) has drained power away from the fundamental political institution upon which democratic control was supposed to be exerted: the state.” What is your definition of sovereignty? How does it inform your work?

Linzey: The people are sovereign. As all of our state constitutions declare, people are the source of all governing authority. But, in reality, that’s the furthest from the truth, of course. The system distrusts democracy, much in the same way that this nation’s founders distrusted democracy. Hence, in our system, there are all kinds of overrides, including corporate “rights” and other protections for property. If anything, under our current system of law, property is sovereign. The more property you own, the more power you can exercise. Part of this work is changing that—restoring an original understanding that community majorities have the power to mandate a shift to economic and environmental sustainability, even when it threatens those power centers who hold large amounts of property.

(Image: celdf.org)

Rural America: CELDF’s work challenges a legal doctrine called Dillon’s Rule,

created by an old corporate lawyer named John F. Dillon (1831–1914)

and adopted by the U.S. Court in 1903. The Rule defines the

relationship between local governments and state legislatures. A

relationship that permits the wave of state preemption we are

experiencing today. As the Supreme Court wrote in 1903:

“Municipal corporations [local governments] are…only auxiliaries of the state for the purposes of local government. They may be created, or, having been created, may be destroyed, or their powers may be restricted, enlarged, or withdrawn at the will of the

[state]

legislature.”

The acceleration of state preemption is a direct progeny of Dillon’s Rule. We see states across the nation preempting localities’ power to provide “sanctuary” for undocumented refugees, make laws in any way impacting employer-employee relations, regulate rent, or ban certain forms of natural resource extraction, etc. Community rights-based organizing challenges the doctrine by asserting that citizens have a basic right to local self-governance that cannot be take away or preempted. As a fellow lawyer, in what ways do you actually respect Dillon? What do you think he understood about law that ultimately made him so successful?

Linzey: The same way we respect the conservative foundations that people generally laughed at in the 1970s, but who have now changed the face of the law—like the Heritage Foundation. Dillon and those foundations worked from the same premise—that the law should service economic growth at all costs, and when law deviated from that, there should be a higher power to reverse it. They had fertile ground from the beginning—building on a foundation of the U.S. Constitution, which is about as anti-democratic a document as has ever been written; elevating the rights of property and commerce above the rights of people, communities, and nature. Dillon and others have simply continued to expand that foundation, and have contoured the law to support that expansion. It’s not hard work, but these folks have gone at in a fervor; and they’re rewarded for it. On the other side are the people’s movements who have gone against that grain over the past 200 years. It’s that work which is the hardest; but it’s that work that must be done if we are to survive.

Rural America: The concept of Rights of Nature is undeniably gaining in popularity. In his September 2015 address to the United Nations Pope Francis said: “It must be stated that a true ‘right of the environment’ does exist.” And in his encyclical on climate change he calls for “The establishment of a legal framework which can set clear boundaries and ensure the protection of ecosystems.” In your view, what is the significance of this popularity, and what message do you have for people interested in the idea of rights for the environment/Nature?

Linzey: To do it. Recently, the Ho-Chunk Nation became the first in the country to recognize the legally enforceable rights of nature into their tribal constitution. This isn’t about gawking while others do it—or treating it as a spectator sport—everyone can do it where they are. Organize a group of people, propose a law to your town council, qualify an initiative. Watch as all of the liberal progressives and others say why you can’t do it, and do it anyway. The planet is waiting for us to get off of our duffs and actually do it.

Back to Thomas Linzey’s Author Page | Back to Anneke Campbell’s Author Page