By Vittorio Frigerio

Anarchist Studies

Volume 26, Spring 2018

In 1912, young Victor Serge (he was then 22 years of age) is sentenced to five years in prison in France. It is the price to pay for having been too close to the group of colourful characters that met in the offices of the anarchist newspaper L’Anarchie. And in particular, for his friendship with members of the so-called ‘Bonnot gang’, the ‘tragic bandits’ whose feats as motorised bank robbers stun the French public and make ‘illegalism’ fashionable within anarchist circles.

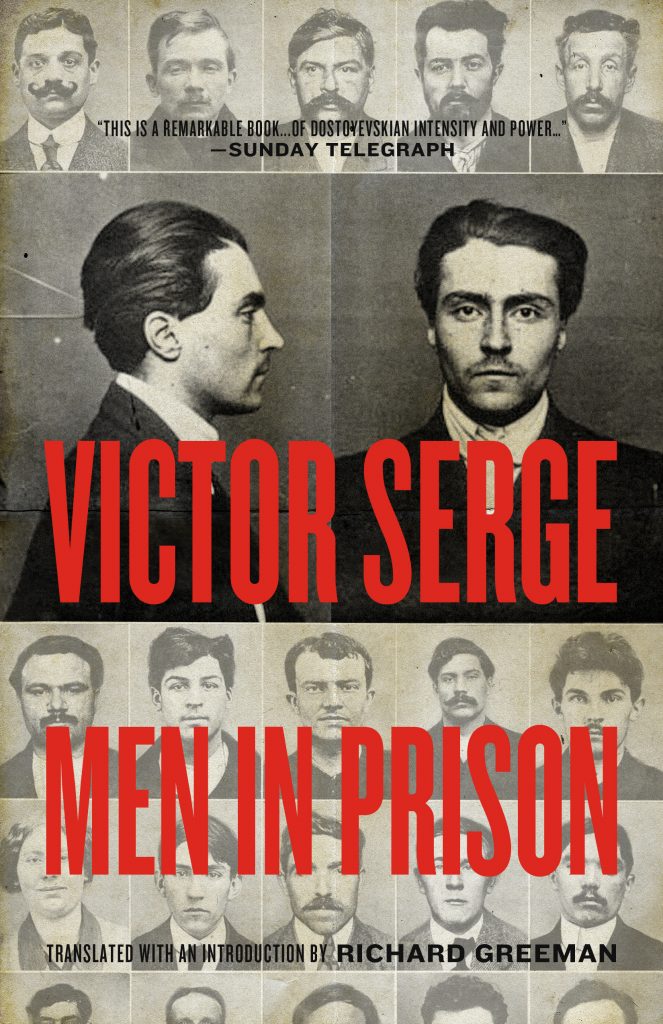

In 1930, living in the Soviet Union, disillusioned with the obvious failure of the Russian Revolution and expelled from the Communist Party, to which he had adhered out of enthusiasm for what seemed at the time like the true way to social progress, Serge takes to writing. Amongst the few volumes he will produce in those years, that will be sent to French publishers as Stalin’s cone of silence has descended upon him, is Men in Prison, a clear-eyed, profoundly humane account of life in the French penal system and of the people Serge met during those five long years – both the prisoners and the various representatives of the state’s repressive apparatus. Thirty-six chapters of varying length give either portraits of fellow inmates, information about the details of everyday life behind bars, or reflections on the effects of forced promiscuity, forced isolation, forced labour and an infinite number of petty regulations that seem designed to make life as unbearable as possible for those caught in the machinery of justice. It is hard to indicate some chapters as being more interesting than others, as they are all marked by the same sober and dispassionate sense of observation, the same strangely distant lucidity, as if what he is talking about happened to somebody else. But it did not, and Serge – in between comments on the prisoners’ obses- sions, dreams and stratagems for survival – also reveals what the experience did for him as a writer, teaching him to see beyond appearances and to guess people’s fate: ‘I, too, learned how to probe the faces and hearts of newcomers. I know if they are going to live […] I read death in them with an awful clarity […] I can’t explain this intuition […] These were not the tricks of a disordered imagination, but the results of keen observations, too complex to be analyzed, as well as of an inner experience confirmed many times over’ (pp114-5).

These are pages that are often very hard to read, and all the more so because the author manages to make his point without ever having recourse to sentimen- tality or trying to tug on the reader’s heartstrings. His descriptions are almost pathologically detached and he lets the facts speak for themselves. One has to wait for the very last pages, when the time comes to tell about his discharge, to find out about his true feelings: ‘The bolts are still locked, but I already feel free, sure of myself; somewhere, within me, there is a calm hatred, like a still ocean. I will turn it into strength’ (p202). Never does this perfectly justified hatred cloud Serge’s portrayal of the banal horrors of prison life. And occasional deadpan remarks highlight the absurdity of the penal system and some truths that the state would rather not advertise: ‘Guards and inmates live the same life on both sides of the same bolted door. Policemen and crooks keep the same company, sit on the same barstools, sleep with the same whores in the same furnished rooms.

They mould each other like two armies fighting with complementary methods of attack and defence on a common terrain I have learned from long experience that, if there are any differences of mentality and morality between criminals and guards or policemen, they are generally, and for profound reasons, all to the advantage of the criminals. Even when it comes to everyday honesty, the compar- ison leads to that conclusion. Most of the guards and policemen I have run into were themselves thieves or crooks, sometimes pimps’ (p37).

Richard Greeman’s translation is flowing and natural, and his introduction will be most useful for those readers who meet Serge for the first time. A foreword by David Gilbert, described as ‘an anti-imperialist political prisoner’ in the US system, shows that things may not have changed as much as one could have hoped since a century ago. Like much of Serge’s other writing, this should be compulsory reading for anybody interested in matters of social justice or in the history of anarchism.

It is also quite simply a great experience for its sheer, great human honesty, that comes across in observations such as this: ‘And isn’t it a kind of fascination mixed with pain that makes me write this book? Old chains which have tortured us dig so deeply into our flesh that their marks become a part of our being, and we love them because they are in us’ (p117).

Back to Richard Greeman’s Author Page | Back to Victor Serge’s Author Page