by Aziz Choudry

wi: journal of mobile media

[T]he world is our classroom, a place full of ideas and

possibilities, and . . . history is replete with examples of how, even

during—and often as a result of—deep-seated crisis, change is eminently possible. – David Austin, 2009 (115)

This

is a discussion—one of many that will take place today—which would not

be happening without the willingness of thousands of people to take to

the streets, put their bodies on the line day after day, for months on

end, and, at the time of this writing, with no apparent end in sight.

For that, I am deeply grateful.

The student strike against

tuition hikes, and the broader mobilizations in Quebec since Bill 78

(the special law against student organizing and protests, among other

draconian measures) passed, highlight the importance of organizing for

social change in difficult times. Longterm efforts at coordination and

education by student organizers and their allies have built and

sustained this major mobilization. It is now viewed internationally as a

major site of resistance against the erosion of rights to education and

the downloading of economic crises onto the middle and working classes

for the benefit of economic and political elites.

These

organization and education efforts are happening in the general

assemblies in which students have been organizing the strike, debating

ideas, making decisions, voting, building strategies and solidarity.

They’re happening in teach-ins and other forums organized by striking

students and in coalition work with other communities and movements to

build connections and common fronts of struggle. They’re happening in

anti-racist organizing within the student movement, challenging racism

and the ongoing marginalization of many racialized students in Quebec.

This mobilization and education has spread to the neighbourhood marches,

casseroles, and popular assemblies springing up across Quebec.

There’s

a lot happening in the streets, every day/every night—incrementally,

incidentally, informally, through talking, exchanging, marching

together, claiming and creating space, confronting power, building

solidarities and trust—learning that could not take place in a

classroom.

Critical adult education scholar John Holst (2002)

writes that “there is much educational work internal to social

movements, in which organizational skills, ideology, and lifestyle

choices are passed from one member to the next informally through

mentoring and modelling or formally through workshops, seminars,

lectures, and so forth” (81). He calls this the “pedagogy of

mobilization” (87).

Theorizing social movements at a level which

is too far abstracted from the dynamics, particularities and

contradictions on the ground has severe limitations. What’s been taking

place across Quebec, in the general assemblies of CEGEP and university

students and in other spaces opened up by this vibrant movement attests

to the potency of “learning from the ground up” (Choudry and Kapoor,

2010). A great deal of knowledge production, learning and theorizing is

taking place in this movement, often occurring under the radar of where

we tend to assume learning and education to take place. As Griff Foley

(1999) notes, profound forms of informal learning may often be

incidental and not even recognized as such, embedded as they are in

social action.

The massive numbers of arrests and violent police

actions against protestors are hard to overlook. This is a movement

which is in turn infantilized, criminalized, brutalized by the state and

sections of the media. For many engaged in this struggle, such conflict

has facilitated profound learning about state power and the limits of

liberal democracy. In thinking these issues through, the insights of the

sociologist and activist George Smith (2006) come to mind.

He

suggests that there is a wealth of research material and signposts

derived from moments of confrontation to explore the way that power in

our world is socially organized. He contends that being interrogated by

insiders to a ruling regime, like a crown attorney, for example, brings

one into direct contact with the conceptual relevancies and organizing

principles of such regimes.

School may be out for summer for many

students, but those concerned with teaching and learning should perhaps

consider the complementarity (and tensions) between formal academic

education, and non-formal and informal learning in this struggle. As

Paula Allman (2001) contends: “Our consciousness develops from our

active engagement with other people, nature, and the objects or

processes we produce. In other words, it develops from the sensuous

experiencing of reality from within the social relations in which we

exist” (165).

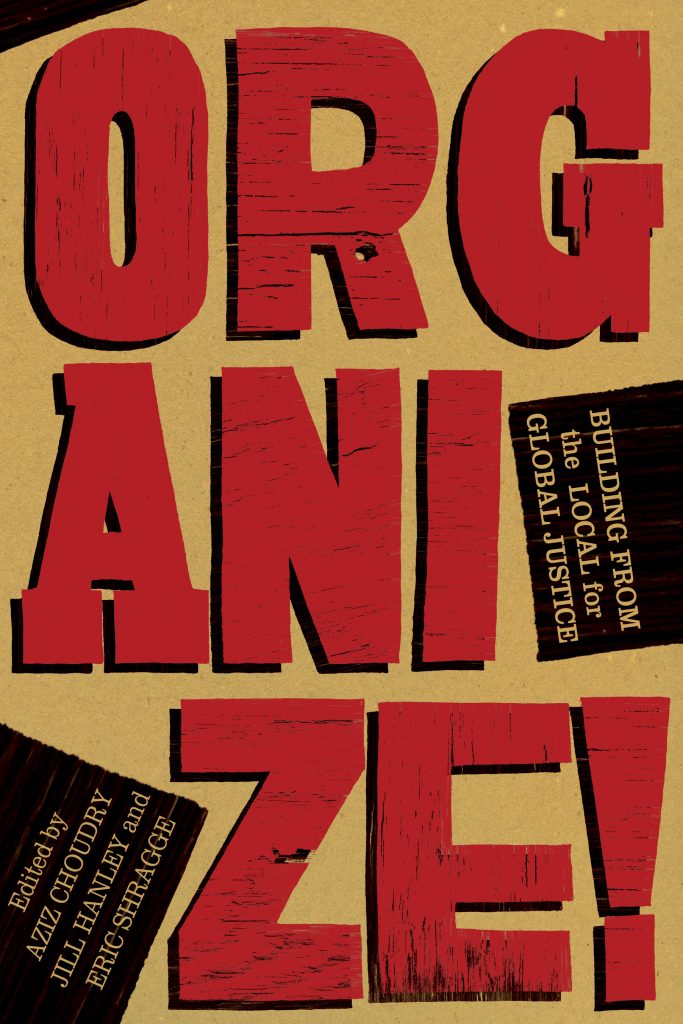

In our new book, Organize! Building from the Local for Global Justice,

Jill Hanley, Eric Shragge and I identify three elements that are key to

effective organizing: analysis, action, and critical reflection on

practice. Without romanticizing the current movement, I have no

hesitation in saying that I come across each of these elements on a

daily basis in my engagement with these mobilizations and student

activists. The Quebec movement is a rich site of critical learning.

Further, the level of engagement, sacrifice and collective struggle

which many thousands of Quebec students have displayed so consistently

is forcing many to re-examine their cynical view of today’s youth as

individualistic and self-absorbed. We cannot predict the course and

outcomes of this movement but the conscientization and politicization of

a generation of students – and their courage in taking action—offers

hope for the future for many people who do not see ‘business as usual’

as a viable option faced with today’s profound economic, political and

ecological crises. Indeed, perhaps as historian Robin Kelley (2002)

suggests . . . the most powerful, visionary dreams of a new society

don’t come from little think tanks of smart people or out of the

atomized, individualistic world of consumer capitalism, where raging

against the status quo is simply the hip thing to do. Revolutionary

dreams erupt out of political engagement; collective social movements

are incubators of new knowledge (8).

References

Allman, P. Critical Education Against Global Capitalism: Karl Marx and Revolutionary Critical Education. Westport, CT: Bergin and Garvey, 2001.

Austin, D. “Education and Liberation.” McGill Journal of Education 44, no. 1 (2009): 107-117.

Choudry, A., Hanley, J., and Shragge, E., eds. Organize! Building from the Local for Global Justice. Oakland.CA/Toronto.: PM Press/Between The Lines, 2012.

Choudry, A., and Kapoor, D., eds. Learning from the Ground Up: Global Perspectives on Social Movements and Knowledge Production. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2010.

Foley, G. Learning in Social Action: A Contribution to Understanding Informal Education. London and New York: Zed Books, 1999.

Holst, J. D. Social Movements, Civil Society, and Radical Adult Education. Westport, CT: Bergin and Garvey, 2002.

Kelley, R. D. G. Freedom dreams: The Black Radical Imagination. Boston: Beacon Press, 2002.

Smith, G. W. “Political Activist as Ethnographer.” In Sociology for Changing the World: Social Movements/Social Research, eds. C. Frampton, G. Kinsman, A.K. Thompson, and K. Tilleczek, pp. 44-70. Black Point, N.S.: Fernwood, 2006.

Back to Aziz Choudry’s Author Page | Back to Jill Hanley’s Author Page | Back to Eric Shragge’s Author Page