By Mel Motel

WIN Magazine

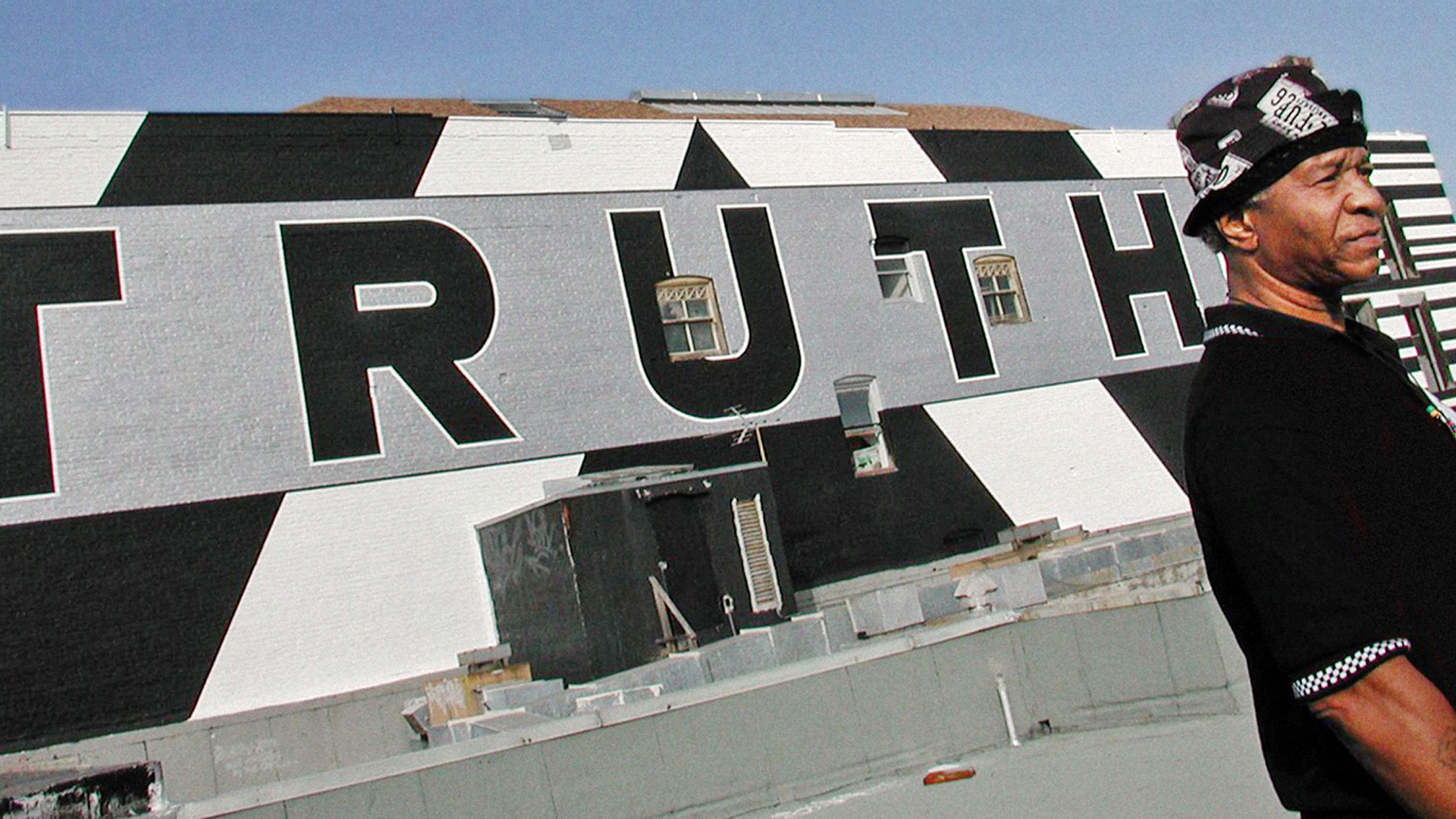

I had the honor of spending some time with the only freed member of the Angola 3 in April 2009 when he swung through Vermont on his book tour. Starting softly, in front of an audience of 60, King grew in volume and intensity as he arrived at the focus of his talk: prisons as an extension of chattel slavery. His style was narrative and circular; he weaved in and out of events and concepts, blending past with present. The first two-thirds of From the Bottom of the Heap resemble this warm, sprawling narrative, mostly reflections on his childhood as he bounces from rural Louisiana to New Orleans, from grandmother to cops to train-hopping hobos.

Three aspects of this book make it accessible and applicable: King’s aptitude for storytelling—non-linear, conversational, straightforward, and insightful—his eventual explanation of the Black Panther Party’s significance and power, and the details of his own legal battles fought from behind prison bars, specifically the appeal that led to his release in 2001 after 29 years of solitary confinement in Angola State Penitentiary, a/k/a “The Last Slave Plantation.”

In From the Bottom of the Heap, King relates his journey as at once remarkable and unremarkable. While his struggle to organize prisoners and steel himself against retaliation is his alone, the circumstances that brought him to Angola and kept him there mirror the experiences of millions of people in this country: the poor, the uneducated, and men and women of color. What King gives the reader is not a lecture but a seasoned account. It is a picture of racism, guard beatings, corruption, torture, favors, snitches, and inhumane living conditions that anyone can identify with who has been locked up or has a loved one in prison.

Where the book falls short is King’s use of the pages as an educational platform. He could have spent more time on political analysis of the Black Panther Party and description of the tactics that he and the other members of the Angola 3—Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox—used to organize prisoners. I also wish the story did not culminate with King’s release from prison but further illuminated the work he has been doing since then to raise awareness about Wallace and Woodfox, who are still in prison.

The legal scholar will find some useful portions, however. Toward the end of the book, King includes a serious, concise account of a civil suit that he won when the Nineteenth District issued a ruling against “routine anal searches.” He also helpfully documents his partially pro se appeal process throughout the 1990s.

When Robert King was released from Angola, he declared, “Even though I was free from Angola, Angola would never be free of me.” With this book, King makes good on his promise. He exposes the horrors of an unjust, brutal system in the hopes that we may all someday be free. King says, “Sometimes, the spirit is stronger than the circumstances.” That he includes “sometimes” is a testament to his honest assessment of reality: that innocence is usually trumped by power. Freedom will not be won without awareness and sacrifice.

Mel Motel came to Vermont in 2006 to help build a restorative justice-based prisoner reentry program. She continues to meet with and advocate for people returning to the community after doing time, works at Prison Legal News, and organizes with Vermont Action for Political Prisoners. This article originally appeared in Prison Legal News. Reprinted with permission.

Back to Robert Hillary King’s Author Page