by Edward Wells,

Professor of Environmental Studies,

Division of Integrated Sciences Wilson College

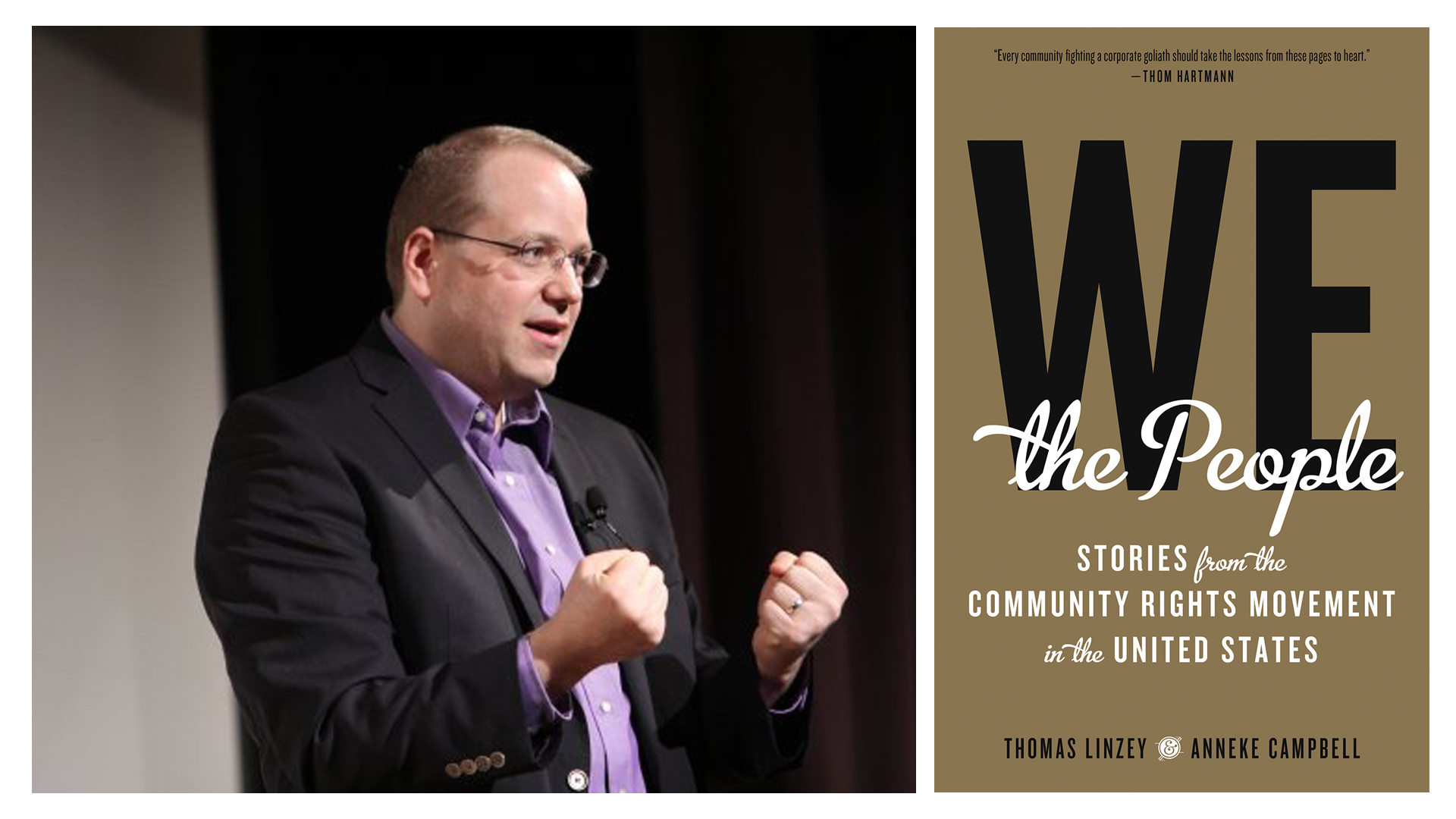

Review of: Thomas Linzey and Anneke Campbell’s We the People: Stories from the Community Rights Movement in the United States

In 1787 the United States Constitution was written beginning with the words, “We, the People of the United States . . .” This document describes how ordinary citizens would govern themselves across the nation. With this democratic deed, the Articles of Confederation were replaced. George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, James Madison and others proposed this document in the face of opposition from Crown loyalists. One of the signers of the Constitution, James Wilson, stresses that the people “retain the right of recalling what they part with . . . . WE [the people] reserve the right to do what we please.” He continues “our governments have been clearly created by the people themselves. The same author that created can destroy; and the people may undoubtedly change the government.” That is, the people reserve the right to revise what they created: ‘WE THE PEOPLE . . ., to secure the blessing of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution . . . “

In their book, We the People: Stories from the Community Rights Movement in the United States, Thomas Linzey and Anneke Campbell suggest the phrase ‘we the people’ in arguing that the democratic spirit has been rebirthed in communities across the United States in the contemporary community rights movement. In these, ordinary people cite “the right to change the law when it no longer functions to protect their communities; they believe they have a duty to do so.” Men and women from such diverse communities as Blaine and Grant Township, PA; Tamaqua and Pittsburgh, PA; Spokane, Washington as well as the states of New Hampshire Colorado, Oregon, and Ohio have claimed their power as citizens. With varying degrees of success, these people have changed their communities. These “ordinary citizens”, just like the writers of the Declaration of Independence and United States Constitution, are committed to the idea that government exists to protect the rights of people and communities, both human and natural. We the People powerfully summarizes struggles of communities as they are engaged in fighting fracking, factory farms, pipelines, coal mining and other activities including fair wages, paid family leave, and others.

For over two decades, Thomas Linzey, founder and Executive Director of the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF) has been representing communities across the country to assist them in reclaiming their sovereign power. In “Democracy Schools”, he and others from CELDF explain that federal and state laws are often not designed to prevent pollution, but to regulate how much pollution should be allowed in our communities. Additionally, federal statutes like the National Environmental Policy Act, which requires Environmental Impact Statements to be written by federal agencies for any activity that may “significantly affect the quality of the human environment”, were never designed to prevent environmentally harmful activities. Rather, NEPA only requires that the environment be “considered.”

The approach of CELDF, rather than working directly on changing government from the top-down (federal–>state–>local) begins at the local (grassroots) level. CELDF helps communities develop ordinances to ban certain unwanted activities. From there, it targets amending state constitutions. The bottom-up change may someday create enough power to eventually amend the U.S. Constitution. Noting that few state constitutions can be changed by ordinary people (state legislators must introduce legislation), people in communities across the country are organizing to address issues in their particular localities.

These modern-day community rights advocates can be compared to the Abolitionists. Abolitionists faced both slave owners and a system of law that protected the practice of slavery. Similarly, communities today face opponents in both corporations and a system of law that protects corporate power from democratic control.

Linzey and Campbell highlight many successes where citizens have taken their rightful power back from corporations and the governments that pander to these corporations. Whereas natural ecosystems are largely still considered property, just as slaves once were, people have fought for the right to have ecosystems, like rivers and forests, to be granted their own rights. As change moves upward from localities to states, five states are organizing networks to enshrine community and ecosystem rights into the federal Constitution.

The book closes with efforts of CELDF to build a rights of nature framework into the Constitutions of other countries. In fact, CELDF worked with legislators to have rights of nature concepts built into the newly revised Constitution of Ecuador of 2008 and continues to work on similar efforts in such diverse nations as Ghana, Cameroon, Kenya, Canada, Spain the United Kingdom and the European Union.

In closing, We the People: Stories from the Community Rights Movment of the United States provides those involved in reclaiming their democratic rights, bestowed upon Americans by the Constitution, to affect change in their communities and improve the quality of life for community members and the ecosystems in which they live. It is a highly recommended read for those wishing to affect change in their communities.

Back to Thomas Linzey’s Author Page | Back to Anneke Campbell’s Author Page