by Almah LaVon

Novel Niche

October 8th, 2016

Who will take us in? This is what Glenda Moore was asking when she

knocked on strangers’ doors for hours in late October 2012. Caught

outside with her young sons in Staten Island, New York during Hurricane

Sandy, she asked this when doors were opened, only to be closed in her

face. (Later, some of the people who refused to help said they thought

she was trying to burglarize their homes.) She asked this until she lost

grip of her sons. Until the sea said, I will take them.

The bodies of Brandon, 2, and Connor, 4, were discovered nearby a few days later.

***

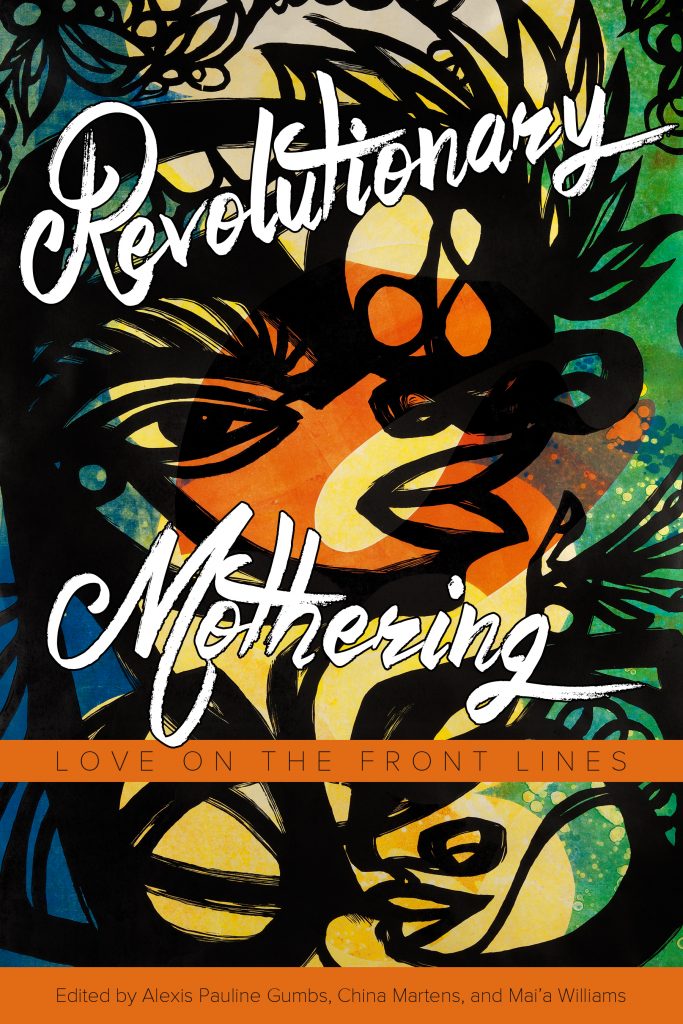

This is how marginalized mothers are unsheltered every day; this is why an arbor-anthology had to be built, and its name is Revolutionary Mothering: Love On The Front Lines (PM Press, 2016). The aim of this collection of communiqués, poems, essays, and visual art is to center mothers, who, like Moore, are locked out of “angel in the house” iconographies–i.e., primarily “radical mothers of color with a few marginalized (queer, trans, low income, single, and disabled) white mothers,” in the framing words of editors Alexis Pauline Gumbs, China Martens, and Mai’a Williams. And how do the editors define mothering? Panoramically. Enter this anthology knowing that there is a new spelling of the name: “m/other.” Spell it like “investing in each other’s existence,” as Loretta Ross does in the brilliant preface. Spell it like “less as a gendered identity and more a possible action, a technology of transformation,” as Gumbs does in her poetic, incandescent essay, “m/other ourselves: a Black queer feminist genealogy for radical mothering.” Spell it like “a primary front in this struggle {against a colonial, racist, hetero-patriarchal capitalism}, not as a biological function, but as a social practice,” as Cynthia Dewi Oka does in one of the book’s most electrifying entries, “Mothering as Revolutionary Praxis.”

“Revolutionary mothering” may be more redundant than oxymoronic, according to the biome of this book. However, Malkia A. Cyril reminds us in her incisive “Motherhood, Media, and Building a 21st-Century Movement,” the weaponized think-of-the-children has been used to undergird “a conservative vision of family” and the carceral state. Cyril asserts:

…empire is sustained, and mothers become one of the tools of its continuous resurrection.

But just as mothers can become the ideological vehicles for hierarchy and dominance, they are uniquely positioned to lead both visionary and opposition strategies to it. With the right supports, mothers from underrepresented communities can help lead the way to new forms of governance, new approaches to the economy, and enlightenment of civil society grounded in fundamental human rights. In fact, they always have.

With blazing authority in “Forget Hallmark: Why Mother’s Day Is a Queer Black Left Feminist Thing,” Gumbs dismisses “the assumption that mothering is conservative or that conserving and nurturing the lives of Black children has ever had any validated place in the official American political spectrum.” (If it was so conservative, why have so many forces been arrayed against it?) Gumbs argues convincingly that Black motherHOOD is fundamentally insurgent; Black mothers, past and present, harbor futurity.

***

Witness the diversity of dispatches from the front lines: in Victoria Law’s “Doing It All…and Then Again with Child,” an organizer-mama writes letters to incarcerated women (many of them also mothers) that incorporate her daughter’s drawings–and travels to Chiapas, Mexico to hear Zapatista mothers talk about seamlessly integrating children into revolutionary struggle. Irene Lara invokes “Tlazolteotl, the Nahua sacred energy of birthing and regeneration” in the ceremony-limned “From the Four Directions: The Dreaming, Birthing, Healing Mother on Fire.”

Mothers construct a theatre of testimony to resist genocide and extrajudicial killings in Arielle Julia Brown’s “Love Balm for My SpiritChild,” reminding me of the indefatigable Asociación Madres de Plaza de Mayo. In Lindsey Campbell’s “You Look Too Young to Be a Mom,” a chorus of young mas flip scripts that insist teen pregnancy is disaster unalloyed. tk karakashian tunchez megaphones “WE ARE WELFARE QUEENS AND WE AREN’T ASHAMED” in the manifesta, “Telling Our Truths to Live.” In “On My Childhood, El Centro del Raza, and Remembering,” Esteli Juarez re-members being raised by a father and other activists who occupied an abandoned school in Seattle, Washington for months, so that Chicanos, Mexicanos, and Latinos could have a public space to “gather, build community, access resources, [and] organize.”

The etymological root of “anthology” is “many flowers,” and Revolutionary Mothering is truly a fistful of spiky, necessary blooms. You need to be present for stories like these: Norma Angelica Marrun reflects on an undocumented childhood in the U.S. without her mother in “Why Don’t You Love Her?” In “Birthing My Goddess,” H. Bindy K. Kang is subjected to reproductive profiling and surveillance targeting South Asians in British Columbia. Terri Nilliasca reveals that the international adoption machine is built for white Westerners, and not balikbayan coming to the Philippines to adopt (“Night Terrors, Love, Brokenness, Race, Home & the Perils of the Adoption Industry: A Journey in Radical Family Creation”).

This book is riven with border lines–indeed, one of its conceits is lines, from “shorelines” to “between the lines”–and those lines matter. Border and bottom lines often mark what kind of mothering one has access to; Gumbs summons “immigrant nannies like my grandmother who mothered wealthy white kids in order to send money to Jamaica for my mother and her brothers who could not afford the privilege of her presence.” Cynthia Dewi Oka adds that “collectivizing caregiving in our communities is linked to dismantling a capitalist empire that abuses Third World women’s bodies as part of its infrastructure.” The children of marginalized mothers in the U.S., Loretta Ross makes clear, are primed to “become disposable cannon fodder for U.S. imperialism.”

There are some lines in the sand, uncrossable uncrossable. Gumbs calls out “neo-eugenicist” rhetoric and its relationship to “globalized ‘family planning’ agendas that have historically forced women in the Caribbean, Latin America, South Asia, and Africa to undergo sterilization in order to work for multinational corporations”; she also quotes officials who suggest that aborting Black fetuses in the U.S. will reduce crime and sterilizing women in “developing nations” will “prevent economically disruptive revolutions.” Oka punctures the population-bomb bogeyman embodied in “Black, indigenous, and Third World children…as perpetrators of environmental degradation.” In fact, mothering and radical homemaking are the imaginarium our moment needs, Oka insists–as she sketches a vision of the homes and habitats to come: “Perhaps the kind of home we need today is mobile, multiple, and underground.” The home as rhizome. A site of flux and disturbance, in the most generative sense. The home of the warning shot, to shoo away the State (see: Korryn Gaines). As an otherworldly realm of revolutionary eclipse and endarkenment: “Perhaps we need to become unavailable for state scrutiny so that we can experiment,” she muses, leaving us with a deepened “encumbrance upon each other while rejecting the extension of our dependence on state and capital.” Isn’t this kind of reliance and resiliency we will need, considering the demands of climate change? Is this what it means to mother in the Anthropocene?

***

Thankfully, this book doesn’t neglect to hold what is unresolved and difficult about mothering and being mothered. There’s pressure on people of color to craft reactive hagiographies about our mothers; while the impulse is understandable–don’t talk about your mother’s failures since the State is all too prepared to enumerate and criminalize them–stories like Rachel Broadwater’s “Brave Hearts” are refreshing. In it, Broadwater meditates on her disappointment with her own traumatized, imperfect mother. Mai’a Williams eschews the soft-focus sentimentality surrounding “mamahood” when she writes, “It’s a visceral sense that vulnerable, quivering life is breaking you and you have to let it. It’s not self-sacrifice. It may not even qualify as love. It isn’t sweet. It isn’t romantic.” This is beautifully and painfully illustrated in Vivian Chin’s essay, “Mothering,” which is mysterious, fraught with slippage, and haunted by damage not quite known. This is the anti-lullaby–this is rage-son, ankle bracelet, juvenile court, polliwogs not getting enough nutrients, you don’t help me with shit. Fabielle Georges’ “The Darkness” flickers with the radioactivity of colorism, lookism, and Black self-loathing. Claire Barrera talks about being short-fused due to chronic pain in “Step on a Crack: Parenting with Chronic Pain.”

***

If this anthology’s foremother is This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color–indeed, its initial title was This Bridge Called My Baby–then its sibling might be the zine movement. China Martens traces a brief history of “subculture media” that includes The Future Generation zine she started in 1990. Several zinesters are featured in Revolutionary Mothering, including Noemi Martinez of the zines, Making of a Chicana and Hermana, Resist. Martens explores how zines oiled her leap to blogs and “online snippets” especially suited to the time-strapped mom. Some of the anthology’s contributions (like Mamas of Color Rising’s “Collective Poem on Mothering”) read like raw, urgent telegraphs from mothers out of time–“time traveling is a necessity,” Martens says–and these seemingly rush-crafted pieces add to the anthology’s sense of welcome and immediacy.

***

Revolutionary Mothering is a

dreambook. Place it on your bedstand and when you awaken, scribble your

not-quite-daylight visions in the margins so your dreams will be in good

company. With its protean take on mothering, expect to pick up a new

book each time you open it. And while we’re dreaming, I would have loved

more voices from mothers who embody the truth that “mother” is “older

and more futuristic than the word ‘woman,’” as Gumbs wrote. Also invoked

by Gumbs, I want more stories from the house mothers of ball culture

themselves. Next time, then. I have gotten into the habit of collecting

radical anthologies, and this one ranks among my favorites: I was rocked

and healed and mothered by this open-armed anthology itself, and

suspect it will go on to give birth to other anthologies, other worlds.

Mothering got next.

If your potential was visible on your body,

like a hologram of your future, you’d know what things to just give up

on without trying . . . but then you’d never know that you change your

hologram potential if you try.

—Rio, Katie Kaput’s nine-year-old son in “Three Thousand Words”

Those caregiving collectives? Those “phamilies, chosen and stronger than blood” tk karakashian tunchez speaks of? Yes, those. We have an amphibious city to build now, and Revolutionary Mothering offers so many blueprints, so much holographic potential. Let’s hold each other close, before the rising seas.

Almah LaVon is a poet errant and incogNegr@ who is often based in western Pennsylvania. More of her writing on books can be found in the forthcoming anthology, Solace: Writing, Refuge, and LGBTQ Women of Color.

Shivanee’s postscript: It’s a tasselated, tapestried honour to have Almah’s critical work on Novel Niche! Many thanks to her, and to the editors and contributors of this formidable anthology, purchasable here.

Back to Mai’a Williams Author Page | Back to Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s Author Page | Back to China Marten’s Author Page