The World View of C.L.R. James

by Noel Ignatiev

Cyril Lionel Robert James was born in Trinidad in 1901 to a middle- class black family. He grew up playing cricket (which he credited with bringing him into contact with the common folk of the island). He also reported on cricket, and wrote a novel, several short stories, and a biography of Captain Cipriani, a Trinidadian labor leader and advocate of self-government. In 1932, James moved to England, where he covered cricket for the Manchester Guardian and became heavily involved in Marxist politics.

He wrote a history of the San Domingo revolution and a play based on that history, in which he and Paul Robeson appeared on the London stage. He wrote a history of the Communist International, The History of Negro Revolt, and translated into English Boris Souvarine’s biography of Stalin. Together with his childhood friend, George Padmore, James founded the International African Service Bureau, which became a center for the struggle for the independence of Africa, helping to develop Jomo Kenyatta, Kwame Nkrumah, and others. He also spent time with coal miners in Wales (among whom he reported he felt no consciousness of race).

In 1938, James came to the United States on a speaking tour, ending up staying for fifteen years. He had discussions with Trotsky in Mexico and took part in the Trotskyist movement in the U.S. While in the U.S., James wrote a study of Hegel and the application of the dialectic in the modern world, a study of Herman Melville, a three-hundred-page outline for a study of American life (later published as American Civilization), and a number of shorter works (including the first of the two in this volume). During World War II he lived among and organized sharecroppers in southeastern Missouri. In 1952 James was arrested and interned on Ellis Island; the following year he was deported from the U.S. (His deportation was perhaps one of the greatest triumphs of McCarthyism: how might history have been different had he been in the country during Malcolm X’s rise?)

For most of the next few years, C.L.R. James lived in the United Kingdom, returning to Trinidad briefly to edit The Nation (the paper of the People’s National Movement) and serve as secretary of the Federal West Indian Labour Party (which advocated a West Indian federation). He left in 1961 after a falling out with Eric Williams, Prime Minister of Trinidad and a former student of James’s, over Williams’s turn toward supporting U.S. imperialism. Before leaving, he delivered a series of lectures aimed at providing the citizens of the new nation with a perspective on Western history and culture; these lectures, which for years were kept locked in a warehouse in Trinidad, have been published under the title, Modern Politics.

In 1968, taking advantage of the rising mood of revolution on the campuses, a group of black American students at Northwestern University brought James to the U.S. There he held university teaching posts and lectured widely until 1980. For the last years of his life, he lived in south London and lectured on politics, Shakespeare, and other topics. He died there in 1989.

In the West Indies, James is honored as one of the fathers of independence, and in Britain as a historic pioneer of the black movement; he is regarded generally as one of the major figures in Pan-Africanism. And he led in developing a current within Marxism that was democratic, revolutionary, and internationalist.

Obviously, this is a great variety of activities for a single individual to undertake. If the word “genius” has any meaning, then it must be applied to C.L.R. James. Most important, however, is not his individual qualities, but the worldview that enabled him to bring light to so many different spheres of activity. James says in Notes on Organization that when you develop a new notion, it is as if you have lifted yourself to a plateau from which you can look at familiar things from a new angle. What was James’s notion, and how did it enable him to make unique contributions in so many areas?

For James, the starting point was that the working class is revolutionary. He did not mean that it is potentially revolutionary, or that it is revolutionary when imbued with correct ideas, or when led by the proper vanguard party. He said the working class is revolutionary and that its daily activities constitute the revolutionary process in modern society.

This was not a new idea. Karl Marx had said, first, that capitalism revolutionizes the forces of production and, second, that foremost among the forces of production is the working class. James, in rediscovering the idea and scraping off the rust that had accumulated over nearly a century, brought it into a modern context and developed it.

James’s project was to discover, document, and elaborate the aspects of working-class activity that constitute the revolution in today’s world. This project enabled James and his co-thinkers to look in a new way at the struggles of labor, black people, women, youth, and the colonial peoples, and to produce a body of literature far ahead of its time, works that still constitute indispensable guides for those fighting for a new world.

James and his co-thinkers focused their attention on the point of production, the scene of the most intense conflicts between capital and the working class. In two trailblazing works, “An American Worker” (1947) and “Punching Out” (1952), members of the Johnson-Forest Tendency led by James documented the emergence on the shop floor of social relations counter to those imposed by management and the union, relations that prefigured the new society.

Not every example James cited was from production. In “Negroes and American Democracy” (1956) he wrote, “the defense of their full citizenship rights by Negroes is creating a new concept of citizenship and community. When, for months, 50,000 Negroes in Montgomery, Alabama do not ride buses and overnight organize their own system of transportation, welfare, and political discussion and decision, that is the end of representative democracy. The community as the center of full and free association and as the bulwark of the people against the bureaucratic state, the right of women to choose their associates as freely as men, the ability of any man to do any job if given the opportunity, freedom of movement and of association as the expansion rather than the limitation of human personality, the American as a citizen not just of one country but of the world – all this is the New World into which the Negro struggle is giving everybody a glimpse…”

That is the new society and there is no other: ordinary people, organized around work and activities related to it, taking steps in opposition to capital to expand their freedom and their capacities as fully developed individuals. It is a leap of imagination, but it is the key to his method. Of course the new society does not triumph without an uprising; but it exists. It may be stifled temporarily; capital, after all, can shut down the plant, or even a whole industry, and can starve out an entire community. But the new society springs up elsewhere. If you want to know what the new society looks like, said James, study the daily activities of the working class.

James insisted that the struggles of the working class are the chief motor in transforming society. Even before it overthrows capital, the working class compels it to new stages in its development. Looking back at U.S. history, the resistance of the craftsmen compelled capital to develop methods of mass production; the workers responded to mass production by organizing the CIO, an attempt to impose their control on the rhythms of production; capital retaliated by incorporating the union into its administrative apparatus; the workers answered with the wildcat strike and a whole set of shop-floor relations outside of the union; capital responded to this autonomous activity by moving the industries out of the country in search of a more pliant working class and introducing computerized production to eliminate workers altogether. The working class has responded to the threat of permanent separation from the means of obtaining life with squatting, rebellion and food riots; this is a continuous process, and it moves the society forward – ending, as Marx said, in the revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes.

James observed the triumph of the counter-revolution in Russia, the crushing of the workers’ movement in Europe by fascism, and the role of the Communist Parties, and he concluded that these developments indicated that capitalism had reached a new stage. This new stage, like every development of capitalist society, was a product of workers’ activity. The labor bureaucracy, that alien force ruling over the working class, grows out of the accomplishments of the workers’ movement. In a modern society like the U.S., the working class struggles not against past defeats but against past victories – against the institutions that the workers themselves have created and which have become forms of domination over them. The social role of the labor bureaucracy is to absorb, and if necessary repress, the autonomous movement of the working class, and it scarcely matters whether it is Communist in France, Labour in Britain, or the AFL-CIO in this country.

“The Stalinist bureaucracy is the American bureaucracy carried to its ultimate and logical conclusion; both of them products of cap- italist production in the epoch of state-capitalism,” wrote James in State Capitalism and World Revolution (1950). In that work he called the new stage state capitalism, a system in which the state assumes the functions of capital and the workers remain exploited proletarians. He said that Russia was this type of society. Others before him had come to similar conclusions. James’s theory was distinctive: it was a theory not of Russia but of the world. It applied to Germany, England, and the U.S. as much as to Russia. He wrote, “What the American workers are revolting against since 1936 and holding at bay, this, and nothing else but this, has overwhelmed the Russian proletariat. The rulers of Russia perform the same functions as are performed by Ford, General Motors, the coal operators and their huge bureaucratic staffs.” This understanding of the “organic similarity of the American labour bureaucracy and the Stalinists” prepared James and his colleagues to see the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, the French General Strike of 1968, and the emergence of the U.S. wildcat strikes of the 1950s and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers in Detroit in 1967 as expressions of a global revolt against the domination of capital.

In an industrial country, it is not the guns and tanks of the government that hold the workers down. When the working class moves, the state is powerless against it. This was true in Hungary in 1956, it was true in France in 1968, and it was true in Poland in 1980. It is not guns and tanks but the relations of capital within the working class, the deals that different sectors of it make with capital, that hold the workers back. According to James, the working class develops through the overcoming of internal antagonisms, not external foes. He saw a civil war within the ranks of the working class and within the mind of each individual worker: two ways of looking at the world, not necessarily fully articulated, manifest in different sorts of behavior. Consistent with this notion, he saw the autonomous activities of groups within the working class as a crucial part of its self-development. As a Marxist, James believed that the working class, “united, disciplined, and organized by the very mechanism of capitalist production,” had a special role to play in carrying the revolution through to the end. But he also believed that the struggles of other groups had their own validity, and that they represented challenges to the working people as a whole to build a society free of the domination of one class over another. In “The Revolutionary Answer to the Negro Problem in the U.S.A.” (1948), he opposed “any attempt to subordinate or push to the rear the social and political significance of the independent Negro struggle for democratic rights.” In that same work, written long before the Black Power movement, James spoke of the need for a mass movement responsible only to the black people, outside of the control of any of the Left parties.

He and his colleagues adopted a similar attitude toward the struggles of women and youth. “A Woman’s Place” (1950), produced by members of the tendency led by James, examined the daily life of working-class woman, in the home, the neighborhood, and the factory, and took an unequivocal stand on the side of women’s autonomy. They brought the same insights to the struggle of youth.

James also paid close attention to the struggle against colonialism. In 1938, he wrote The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution. In that work he spoke of the tremendous creative force of the colonized peoples of Africa and the West Indies, and established the link between the masses of San Domingo and the masses of Paris.

His appreciation of the struggles of black people, of women, of youth, of the colonial peoples expressed his dialectical thinking. Here you have this revolutionary working class, said James, and at the same time you have the domination of capital, which also expresses itself within the working class. One of the places this conflict appeared was in culture.

The dominant tradition among Marxists held that popular culture is just brainwashing, a distraction from the class struggle. To James and his co-thinkers, the point was: how do the outlines of the new world manifest themselves in culture? In Mariners, Renegades and Castaways: The Story of Herman Melville and the World We Live In (1953), James demonstrated that the struggle for the new society was a struggle between different philosophies as they are lived. (It is my personal favorite among his works; among other virtues, it offers the most exciting explanation I have ever read of the process of literary creation.) His autobiographical book on cricket, Beyond a Boundary (1962), was not merely a sports book. It was about the people he knew intimately in the West Indies, and how their actions on the playing field showed the kind of people they were. There is a need for a similar study of basketball and the Afro-American people. Anybody can write about how black athletes are exploited by the colleges and later on by professional basketball and the TV and the shoe manufacturers – and all that is true. But for James the question was, How have the black people placed their stamp on the game and used it to express their vision of a new world?

Consider the figure of Michael Jordan in this light. Here is a person who has achieved self-powered flight. Every time he goes up with the ball, he is saying in your face to the society of exploitation and repression. His achievements are not his alone, but the product of an entire community with a history of struggle and resistance. The contrast between the general position of the Afro-American people, pinned to the ground, and the flight they have achieved on the basketball court is an example of the new society within the shell of the old. (I wrote this paragraph in 1992; since then, a book has appeared that does for basketball what James did for cricket: Hoop Roots by John Edgar Wideman. Wideman has said he wrote it with a copy of Beyond a Boundary on his desk.)

The task of freeing that new society from what inhibits it led James to a certain concept of organization. It has been asserted that James opposed organization – more particularly, that he opposed any form of organization that assigned distinctive tasks to those who sought to dedicate their lives to making revolution. The general charge is easily refuted: James spent his whole life building organizations of one kind or another, from the International African Service Bureau in Britain to a sharecroppers’ union in Missouri to the Workers and Farmers Party in Trinidad. The function of these organizations was not to “lead the working class” but to accomplish this or that specific task. The more particular charge requires closer examination.

James argued that, in industrial societies, in which the very mechanism of capitalist production unites, disciplines, and organizes the working class, in which people take for granted modern communications and mass movements, the idea that any self-perpetuating group of people can set itself up to lead the working class is reactionary and bankrupt. In other words, he was a determined opponent of the vanguard party idea. But he did more than curse the Stalinists (and Trotskyites, whom he called “the comedians of the vanguard party”): in Notes on Dialectics: Hegel, Marx, Lenin (1948), he analyzed the organizational history of the workers’ movement, and showed that the vanguard party reflected a certain stage of its development.

In that same work, James anticipated the new mass movements (France, Poland) that would erase the distinction between party and class. (He did not oppose the vanguard party for peasant countries, where he thought something like it might be necessary to mobilize and direct the mass movement – but even there he searched for ways to expand the area of autonomous activity. Nkrumah and the Ghana Revolution, a collection of articles and letters he wrote between 1958 and 1970, shows James grappling with the problem of leadership in a country where the forces of production are undeveloped. It is the least satisfying of his works.)

In modern society, whoever leads the working class keeps it subordinated to capital. A revolutionary crisis is defined precisely by the breakdown of the traditional institutions and leadership of the working class. James argued that it was among the sectors of society least touched by official institutions that relations characteristic of the new society would first appear. It is not the job of the conscious revolutionaries to “organize” the mass movements; that is the job of union functionaries and other bureaucrats.James’s rejection of the vanguard party, however, did not lead him to reject Marxist organization. For proof, one need only recall the great attention and energy he dedicated to building Facing Reality, an avowedly Marxist organization headquartered in Detroit with branches around the U.S. (These efforts are recounted and documented in Marxism for Our Times: C.L.R. James on Revolutionary Organization, edited by Martin Glaberman.) But what would the Marxist organization do? This is where it gets difficult. I once asked him that question and got from him the reply, “Its job is not to lead the workers.” Very well, I said, but what was it to do? For an answer, I got the same: It was not to act like a vanguard party. It was obvious that James was not going to elaborate with me, a person who might for all he knew carry with him the vanguardist prejudices of the “left” he had been fighting for decades. I would have to extrapolate the answer from his works. To these, then, I turned.

In Facing Reality, coauthored by James, Grace Boggs and Cornelius Castoriadis, in the section “What To Do and How to Do It,” it says, “Its task is to recognize and record.” That is a start. Over the next few pages, Facing Reality lays out a plan for a popular paper that will document the new society as it emerges within the shell of the old. As should surprise no one, it is most concrete when discussing what was then called “The Negro Question in the United States”:

For the purpose of illustrating the lines along which the paper of the Marxist organization has to face its tasks (that is all we can do), we select two important issues, confined to relations among white and Negro workers, the largest sections of the population affected.

1) Many white workers who collaborate in the most democratic fashion in the plants continue to show strong prejudice against association with Negroes outside the plant.

2) Many Negroes make race relations a test of all other relations…

What, then, is the paper of the Marxist organization to do?…

Inside such a paper Negro aggressiveness takes its proper place as one of the forces helping to create the new society. If a white worker… finds that articles or letters expressing Negro aggressiveness on racial questions makes the whole paper offensive to him, that means it is he who is putting his prejudices on the race question before the interests of the class as a whole. He must be reasoned with, argued with, and if necessary fought to a finish.

How is he to be reasoned with, argued with, and if necessary fought to a finish? First by making it clear that his ideas, his reasons, his fears, his prejudices also have every right in the paper….

The paper should actively campaign for Negroes in the South to struggle for their right to vote and actually to vote…. If Negroes outside of the South vote, now for the Democratic Party and now for the Republican, they have excellent reasons for doing so, and their general activity shows that large numbers of them see voting and the struggle for Supreme Court decisions merely as one aspect of a totality. They have no illusions. The Marxist organization retains and expresses its own view. But it understands that it is far more important, within the context of its own political principles, of which the paper is an expression, within the context of its own publications, meetings, and other activities in its own name, within the context of its translations and publications of the great revolutionary classics and other literature, that the Negroes make public their own attitudes and reasons for their vote. [Published 1958; given the massive disenfranchisement of black people in 2000, 2004 and 2008, which no major or minor candidate has chosen to make an issue, it might not be a bad thing if revolutionaries, without abandoning their view of the electoral system, were to join in a campaign on behalf of prisoners’ right to vote – NI.]

Such in general is the function of the paper of a Marxist organization in the United States on the Negro question. It will educate, and it will educate above all white workers in their understanding of the Negro question and into a realization of their own responsibility in ridding American society of the cancer of racial discrimination and racial consciousness. The Marxist organization will have to fight for its own position, but its position will not be the wearisome repetition of “Black and White, Unite and Fight.” It will be a resolute determination to bring all aspects of the question into the open, within the context of the recognition that the new society exists and that it carries within itself much of the sores and diseases of the old.

While the above passage focuses on the role of a paper, it provides a guide for other aspects of work. James’s approach was in the best tradition of Lenin (whom James much admired). Lenin, it must be remembered, did not invent the soviets (councils). What he did, that no one else at the time was able to do, not even the workers who invented them, was to recognize in the soviets the political form of the new society. The slogan he propagated, “All Power to the Soviets,” represented the intervention of the Marxist intellectual in the revolutionary process. In basing his policy on the soviets, those “spontaneous” creations of the Russian workers, he was far removed from what has come to be understood as vanguardism.

I recall once in the factory, a group of workers walking out in response to a plant temperature of one-hundred degrees-plus with no fans. Our little group, schooled in the teachings of James and Lenin, understanding that the walkout represented a way of dealing with grievances outside of the whole management-union contract system, agitated for a meeting to discuss how to make that walkout the starting point of a new shop-floor organization based on direct action. That was not vanguardism but critical intervention.

Another example from personal experience: I once worked a midnight shift in a metalworking plant. There were two other workers in the department on that shift, Jimmy and Maurice. Maurice had been having money troubles, which caused him to drink more than he should, which led to missed days and more trouble on the job, which led to troubles at home, etc. I came to work one night after missing the previous night, and Jimmy told me that Maurice had brought a pistol to the plant the night before, planning to shoot the general foreman if he reprimanded him in the morning about his attendance. “Did you try to stop him?” I asked. “No, what for?” queried Jimmy. “What happened?” I responded. “When the foreman came in,” explained Jimmy, “instead of stopping to hassle Maurice, he just said hello and kept going to his office. He doesn’t know how close he came to dying.”

I, of course, did not want Maurice to shoot the general foreman because I did not want him to spend the rest of his life in prison for blowing away an individual who was no worse than the generality of his type. Jimmy looked at matters differently: for him, Maurice’s life was already a prison that could be salvaged by one dramatic NO, regardless of the consequences. Who was right? Well, I had read all the books and knew that ninety-nine times out of a hundred nothing would come of Maurice’s action: the plant guards or the cops would take him away or kill him on the spot. But on the hundredth time, something different might happen: the workers would block the plant guards, fight the cops, and the next thing you knew you had the mutiny on the Potemkin. The new society is the product of those two kinds of knowledge, Jimmy’s and mine, and neither could substitute for the other. As a person who had decided to devote his life to revolution, my job was to Recognize and Record the new society as it made its appearance.

In 1969, a black worker at a Los Angeles aircraft plant, Isaac (“Ike”) Jernigan, who had been harassed by management and the union and then fired for organizing black workers, brought a gun to work and killed a foremen; then he went to the union hall and killed two union officials. Our Chicago group published a flyer calling for workers to rally to his defense. Not much came of it until… the League of Revolutionary Black Workers in Detroit reprinted our flyer in their paper. A Chrysler worker, James Johnson, responding to a history of unfair treatment including a suspension for refusing speedup, killed two foremen and a job setter, and was escorted from the plant saying “Long Live Ike Jernigan.”

The League waged a mass campaign on Johnson’s behalf, including rallies on the courthouse steps, while carrying out a legal defense based on a plea of temporary insanity. The high point of the trial came when the jury was led on a tour through Chrysler; it found for the defense, concluding that working at Chrysler was indeed enough to drive a person insane. (This was Detroit, and many people already knew that to be true.) Johnson was acquitted and sent to a mental hospital instead of to prison; as an added insult, Chrysler was ordered to pay him workmen’s compensation. Such was the political power contained in the simple words, Recognize and Record.

The task of revolutionaries is not to organize the workers but to organize themselves – to discover those patterns of activity and forms of organization that have sprung up out of the struggle and that embody the new society, and to help them grow stronger, more confident, and more conscious of their direction. It is an essential contribution to the society of disciplined spontaneity, which for James was the definition of the new world.

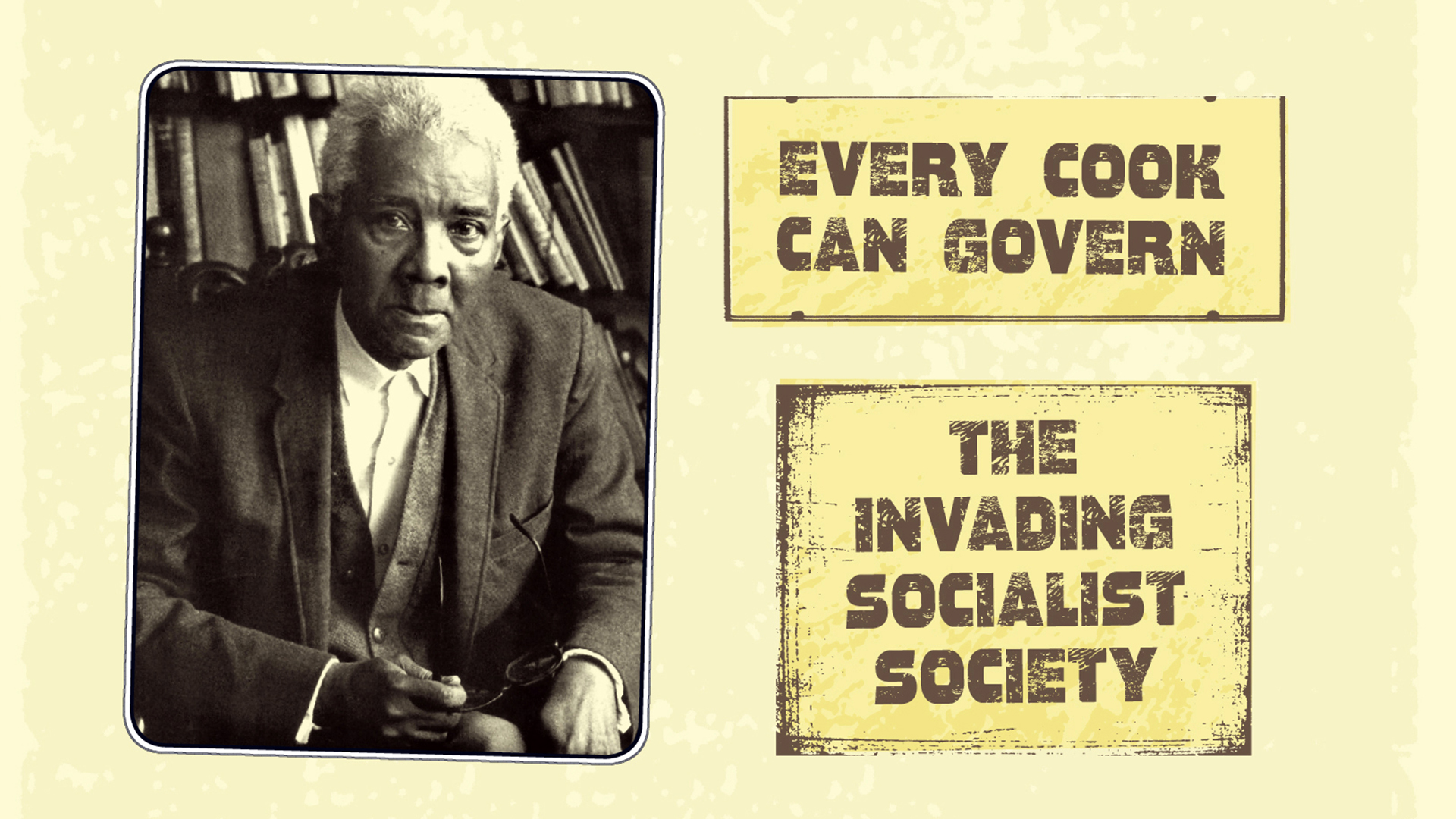

The two works that follow illustrate James’s worldview. The Invading Socialist Society was published in 1947 under the authorship of James, F. Forest (Raya Dunayevskaya) and Ria Stone (Grace Lee Boggs) as part of a discussion within the Trotskyist Fourth International. Inevitably it bears the marks of its birth, and some readers will be put off by the unfamiliar names and context. That would be unfortunate. As James wrote in his preface to the 1962 edition, “The reader can safely ignore or not bother himself about the details of these polemics, because The Invading Socialist Society is one of the key documents, in fact, in my opinion it is the fundamental document” of his political tendency. I shall not attempt to list its main points, but merely urge readers to note the astonishing degree to which it anticipated subsequent events, including the French General Strike of 1968 and the Polish Solidarity of 1980, which together marked the transcendence of the old vanguard party by the politicized nation, and the collapse of the Soviet Union and its satellites, and with it the collapse of the illusion that there ever existed more than one world system.

The second document, “Every Cook Can Govern,” published in 1956 and written for a general audience, was equally prophetic. It is short enough, and rather than attempt to list its main points, I urge readers to read it bearing in mind the counterposing of representative and direct democracy that became so important to SNCC and other components of the New Left of the 1960s (best described in chapter 14 of Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael by Stokely Carmichael and Ekwueme Michael Thelwell).

Together, these two works represent the principal themes that run through James’s life: implacable hostility toward all “condescending saviors” of the working class, and undying faith in the power of ordinary people to build a new world.