by Keith Riley

Maximum Rock’n’Roll

April 2018

About a year ago, I visited the Oakland Museum’s great Power to the People: Black Panthers at 50 exhibit. I felt the showing was important in terms of re-writing the Panthers’ past and emphasizing the ways that the Party’s politics and community programs transformed peoples’ lives in profound ways. The way I figured it – normal people go to the Oakland Museum. If those people chose to pay attention, the Black Panthers would suddenly become much more than the image of the gun-touting radical so commonplace in historical depictions. This is because the exhibit mostly highlighted the Party’s community-oriented, Survival Programs as the most important aspect of the Party’s legacy. An aspect of the Party more palatable to liberal audiences. The Museum’s interpretation, of course, isn’t totally wrong. Survival Program like the Free Breakfast Program, the Community Ambulance Program, and others were a big deal. Yet, the Panthers were an ideologically diverse group, and that insurrectionary impulse of the gun-touting radical remained a significant tenant of many members’ political thinking as well. One could argue that just focusing on the Party’s Survival Programs really misses a lot.

Nowhere is this more apparent than the case of the New York 21, a group of Panthers brought up on conspiracy charges to blow up an NYPD precinct in 1969. The group was later acquitted on all charges in 1971 and the trial remains an important example of the Federal Government’s efforts to dismantle the Party. But, to me, maybe the most interesting aspect of the case was the time that it occurred. The acquittals emerged during a period of significant Party disunity between the factions of Huey Newton and Eldridge Cleaver. While Cleaver was pushing for guerrilla warfare to be waged against the U.S. government, Newton insisted on focusing on Survival Programs. In 1971, following their acquittal, the New York 21 published numerous communiqués pushing for armed struggle against the U.S. government. And, in response – Huey Newton promptly expelled them from the Party. Following their removal from the Black Panthers, key members of the New York 21 like Sundiata Acoli, Kuwasi Balagoon, and Sekou Odinga would join other New York former-Panthers like Assata Shakur in founding the Black Liberation Army, a group of black militants covertly waging guerrilla war against the U.S. government throughout the 1970s and early 1980s. Their story is an important one, yet one that remains seldom told, as it runs in the face with the community programs-centered notion of the Party.

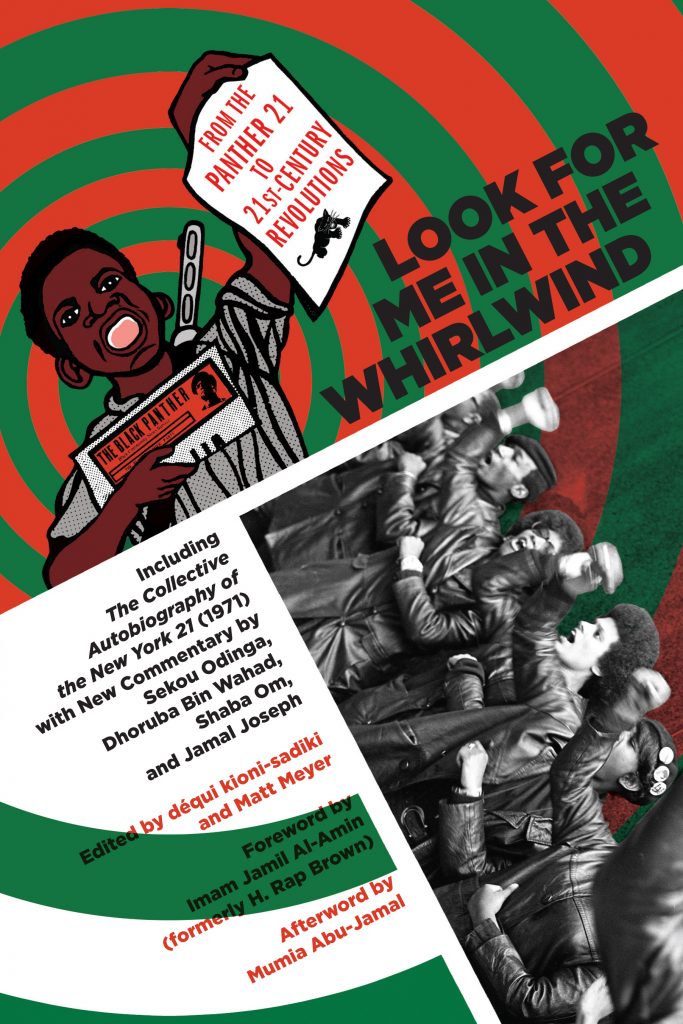

With this historical gap in mind, Look for Me in the Whirlwind, a new collection of writings by New York 21 defendants edited by Matt Meyer and dequi kioni-sadiki, seeks to restore the most militant wing of the Black Panther Party to its proper place amidst the pantheon of other important black leftist writers and thinkers. The book features the writings of Sundiata Acoli, the eighty year old revolutionary still incarcerated due to charges relating to an armed altercation with New Jersey State Troopers in 1973, Afeni Shakur, the New York 21 defendant and mother of Tupac Shakur, Kuwasi Balagoon, Jamal Joseph, and others. Yet, most prominently, the book features a re-pressing of the 1971 collective autobiography of the New York 21 also titled Look for Me in the Whirlwind. Learning this history from the perspective of activists themselves provides readers with a more intimate and personalized look at an important event in the history of the Black Panther Party.

Examining the stories of New York 21 defendants from the historical hindsight of 2017 reveals the diverse political developments of activists whose efforts would greatly impact the struggle for anti-capitalist black liberation throughout the 1970s and 1980s. For me, it’s difficult to read these activists’ stories outside their eventual excommunication from the Party and development of the Black Liberation Army, but I also think that frame makes their stories that much more interesting and important. In developing their inclination towards armed struggle, activists did not solely become politicized through exposure to poverty, street violence, and police brutality, but also through political activism in prisons and international anti-capitalist, guerrilla struggles. These are political factors often obscured in other studies of the Panthers’ political development, yet Look for Me in the Whirlwind in many ways works to place these important influences at the forefront of its analysis.

Defendant Kwando Kinshasa writes of his politicization not taking place on the streets of Harlem, but on the streets of Guatemala City. During the early 1960s, Kinshasa was stationed as a marine in the Central American country. While in Guatemala, Kinshasa befriended the Marxist guerrillas of Movimiento Revolucionario-13, a group fighting the country’s military dictatorship established in the aftermath of the CIA’s overthrow of progressive Guatemalan leader Jacobo Arbenz. “Many of the tactics one would or could use in an urban guerrilla situation were already thoroughly planned in Guatemala, but some priority action was also planned: my Guatemalan friends explained to me that the only way the revolution could succeed would be to educate the masses first, in a period of two, five, ten years or so, to the necessity of armed revolution throughout all of the country,” writes Kinshasa. (p. 388) In this sense, the New York 21 defendants’ exposure to international struggles gave them a differing outlook on the Party’s trajectory. For Kinshasa, the survival programs remained important educational and politicization projects. Yet, the programs were not an end in and of themselves. For him, they had to lead somewhere.

The book also shows the struggle of the New York 21 as not solely limited to the city streets of Harlem and the Bronx, but also extending into the confines of New York City’s jails. As much of the group remained unable to pay their extraordinarily high $100,000 bail, they took to organizing in the Queens Dentention Center, staging a prison rebellion there in 1970. Much like prison abolitionists today, New York 21 defendants viewed the prison system as an extension of the slave plantation, opposing the system on those grounds. Look for Me in the Whirlwind examines the prison as a space that extracts black labor for capitalist profit while severely limiting the movement and livelihood of those imprisoned, simultaneously communicating the ways that activists have historically undermined the system’s exploits. While the Panthers’ prison abolition work is often overshadowed by the Party’s anti-police organizing and community programs, Kuwasi Balagoon’s telling of the 1970 Queen Detention Center uprising and other featured abolitionist writings show the undermining of the U.S. prison system to be an important aspect of the Black Panthers’ and the emerging Black Liberation Army’s political legacy. The fact that many Panthers still remain imprisoned today on charges relating to their activism only further demonstrates the essential nature of this aspect of Panther politics.

Look for Me

in the Whirlwind and its telling of the New York 21’s story presents an

aspect of the Black Panthers’ politics often overshadowed in their

modern day reclaiming by more liberal-minded activists – their

commitment to armed struggle. Writing like “We are madder than hell…

We don’t for sympathy. We ask for vengeance” might make liberals who

have recently accepted the Panthers’ place as an essential Civil Rights

organization somewhat uncomfortable.

(p. 481) Yet, the notion of the

Panthers as solely a group that served breakfast to children or set up

health clinics is too simple. As Look for Me in the Whirlwind shows,

these community-minded activists were armed insurrectionaries, hell-bent

on overthrowing the government, as well. This is an essential part of

the Panthers’ legacy. The New York 21 represent the Panthers at their

most ideologically left position and because of this, their story often

remains obscured.

Look for Me in the Whirlwind works to position the New York 21 as a story essential to the black freedom struggle. To place names like Kuwasi Balagoon, Sundiata Acoli, and Afeni Shakur alongside those of Huey Newton and Elaine Brown. While, by the 1970s, the New York 21’s politics greatly differed from that of the Oakland-based Party headquarters, the story of these activists helps to give readers a more complete picture of the Panthers’ political legacy.

Because of this, Look for Me in the Whirlwind remains essential reading for anyone seeking to understand both the Black Panthers in all their complexities, as well as the emerging politics of the Black Liberation Army.

Back to Sekou Odinga’s Author Page | Back to Dhoruba Bin Wahad’s Author Page | Back to Jamal Joseph’s Author Page | Back to Matt Meyer’s Editor Page