By Michael Heaton

Cleveland Plain Dealer

February 4th, 2015

Randal Doane, 46, is Oberlin College’s assistant dean of studies, responsible for academic advising and coordinating leaves and withdrawals for students. He also oversees a peer adviser program for first-year students and the senior symposium, a one-day conference in April featuring 50 seniors presenting their research to the campus.

He is in his ninth year at Oberlin College, and has lived in Oberlin for 15. He has a wife, and 10-year-old daughter. He also claims “amateur bike mechanic” as a hobby.

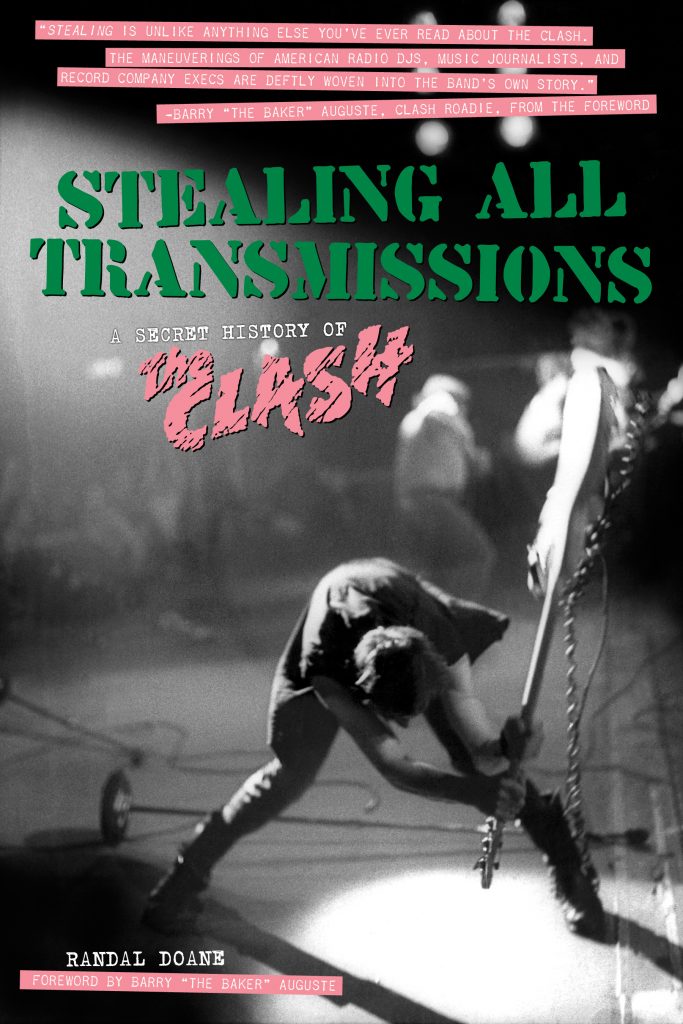

Doane also is the author of “Stealing All Transmissions: A Secret History of the Clash.” The English punk band — the classic lineup includes Joe Strummer, Mick Jones, Paul Simonon and Nicky “Topper” Headon — became widely known as “The Only Band That Matters” in the 1980s, influenced a generation of musicians who followed and were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2003.

Doane recently gave a talk on his book at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Archive. Doane spoke with Plain Dealer reporter Michael Heaton.

Q: When did the book come out?

A: October 2014.

Q: What kind of reviews has it gotten?

A: Los Angeles magazine listed “Stealing” among their best-of-2014 books on music, and I figure I’m the only writer to secure high praise in Counterfire, a socialist magazine, and PJ Media, a bastion for American conservatism. The reviewers who understand that it’s not a Clash biography review it quite favorably.

Q: How did your membership in the Boy Scouts at age 13, in Stockton, California, bring you to The Clash?

When I was 13, I toured Europe and England with the Boy Scouts of America, and the eldest son of my host family in Coventry, England, made me a mix tape with tracks by The Specials, The Selecter, Echo and the Bunnymen, and The Clash. Once I returned to the states, and learned more about the do-it-yourself ethos of punk, my days as a scout were numbered.

Q: Did you ever see them play live?

A: I didn’t, alas. My best opportunity to see The Clash was in Stockton, in 1984, after Mick Jones and Topper Headon had been kicked out of the band. I took a pass. I can’t tell you why exactly, since nearly everyone in my high school went to the show. Maybe it’s because nearly everyone in my high school went to the show.

Q: Do you remember some flash point at which you knew you had to write this book?

A: I had some interest from The New Yorker about a 10,000-word version of this story, but not sufficient interest, apparently. (I understand getting rejected by The New Yorker is not an exclusive club.) After that, I did some more research, conducted more interviews, and produced what I believe is a tidy 130-page book.

Q: You have a PhD. Was it difficult to shake a scholarly writing style when writing this book?

A: Um, no. I’ve always written with the hopes of being understood.

Q: Are you a secret punk in academic clothing?

A: If I told you, it wouldn’t be a secret.

Q: What in your opinion is the funniest scene in the book?

A: That’s a good question, and a difficult choice. The Clash and their entourage were full of compelling, hilarious characters, and seemed to bring out those qualities in their primary handlers at Epic (Records), too. One scene that’s particularly fun entailed Dan Beck and Bob Feineigle at Epic Records doing an end-around on the staff in charge of product management for black radio, in order to get the song “The Magnificent Seven” to the local stations, including WBLS. Lo and behold, when The Clash came to New York in May 1981 for a three-week residency, WBLS had “The Magnificent Seven” in heavy rotation. There are good tales of mayhem in Barry “The Baker” Auguste’s foreword, too.

Randal Doane is the author of “Stealing All Transmissions: The Secret History of the Clash.” Courtesy of Randal Doane

Q: Why do you think living band members didn’t want to talk to you about the book?

A: I decided not to contact the living members of the band, actually. There is so much material in the archives and in great books about that era, and I’m confident that those materials are likely more accurate than the memories of Messrs. Jones, Simonon, and Headon. Also, each tale recounted to me by Barry “The Baker” Auguste, former back line roadie for The Clash (and author of the foreword), checked out perfectly. I couldn’t have asked for a better comrade in the trenches of punk historiography.

Q: What was so special about The Clash that brings them such fevered following to this day?

A: I like Robert Christgau’s description of The Clash as “politically effective and aesthetically effective.” Their politics were great, from the get-go to the not-quite-glorious end, and they grew so much musically from album to album, thanks especially to Mick Jones and Topper Headon. Headon could play in any style, and that made it possible on “London Calling” for them to perform rock steady, reggae, ska, and straight ahead rock ‘n’ roll, and on “Sandinista!” to perform dub, hip-hop, disco, and soul tunes. Minus some of the filler on “Sandinista!” that’s eight great album sides in 12 months. Who else has come close?

It’s not just

the music, though. Strummer especially wanted to get to know their

fans, and — like good punks — The Clash rejected the growing divide

between performers and fans that plagued the stadium rock acts of the

late 1970s. In terms of that ethos: they started out that way, and

ended that way. I wish there was more footage from their last gigs

together, when they hit the road in England with plenty of guitars and

no money (by choice), and they had to busk for their daily keep.

Q: What was so important about the free format NYC radio scene in the ’70s that made the Clash’s success possible?

A: Free-form radio started in the late 1960s, and WNEW in New York City had some of the biggest names in radio through the 1970s and 1980s. These guys played The Who, Sinatra, John Coltrane, readings by Shel Silverstein, and one of the key programs at WNEW was their “Live at the Bottom Line” series. It got started with Melissa Manchester, featured Bruce Springsteen just before the release of “Born to Run,” and in 1976 included shows by a young Billy Joel, Donovan, and Jerry Jeff Walker — the “Mr. Bojangles” guy. Meg Griffin joined the station in 1977 while she was in her mid-20s, and she would go to concerts at CBGB and elsewhere and, on her overnight shift, fill the airwaves with tracks by Talking Heads, Television, Blondie, and even The Clash. Her fellow DJs resisted it at first, but she kept playing punk, as did DJs at WLIR. And local rock scribes started writing about great discs from local bands and stuff arriving on import, and the fan base for The Clash and punk writ large kept growing. So, with The Clash coming back to New York for the second time in 1979 to play two shows at The Palladium, it was an easy sell for Harvey Leeds of Epic Records to get WNEW to do a live simulcast that reached from Philadelphia to southern Connecticut.

Q: Why is the subtitle the SECRET history of the Clash? Why is it secret?

A: It’s logical for punk history fans to make the connection between “Stealing” and Greil Marcus’ brilliant “Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the 20th Century,” which includes some of the best writing on punk ever. I had “The Secret History,” a novel by Donna Tartt, in mind when I came up with the title, actually. It’s a secret of sorts since the big biographies on The Clash (Pat Gilbert’s is my fave) effectively missed this story, as did Marcus Gray in his 560-page book about “London Calling.”

Q: How difficult was it to get permission from Pennie Smith to use her iconic photo from the cover of “London Calling” as the cover of your book?

A: The difficulty was in finding Pennie, actually, and once that happened, and we got to talking, she was happy to license my use of the greatest photograph in rock history.

Q: What new music do you like? Are you still actively listening to the new?

A: I’m a big fan of Hamell on Trial, and I just picked up Sleater-Kinney’s new LP on vinyl. I listen to stuff my 10-year-old daughter likes, too, including St. Vincent, Santigold, Rubblebucket, and The Julie Ruin.

Q: How does the music we listen to today have an influence on the written word and is that any different than when the Clash was coming up?

A: The digital era is fantastic, don’t get me wrong. The quantity of good music today is astounding. In the final years of the analog era, there was simply less music and less writing about music and, depending upon where you lived, less access to both. So, if your tastes were not mainstream, it was easier to construct a consensus of fellow listeners and readers around bands like The Clash, and bands on the SST, IRS, or 4AD labels. Today, the access is phenomenal, but I believe these conditions don’t foster the devoted, repetitive listening and depth of fandom when you’re listening to one, maybe three, new LPs at a time.

Q: Why do you think the Clash broke up?

A: In part, I suspect, because they never took a break. It was tour, rehearse, record, and tour, rehearse, and record. I think this was Strummer’s doing, but Jones worked seven days a week during the lead-up to “London Calling.” Had they taken a break early on, maybe Headon would have pursued proper treatment for his drug problem, and maybe Jones wouldn’t have been so chronically difficult. “Rock ‘n’ roll Mick” was not an easy guy to work with, but music-wise, he brought the goods.

Q: Are you working on another book?

A: I’m working on a screenplay adaptation of “Stealing,” hoping to cast Justin Bieber as the young Joe Strummer — just kidding, Clash-o-philes! Seriously, though: If The Specials’ Jerry Dammers were to inquire about collaborating on his memoir, I’d sign on in a heartbeat.