By Christian Belanger

Chicago Reader

April 17th, 2019

The UIC prof and former factory worker has no nostalgia for the days of middle-class manufacturing jobs.

In the mid-70s, David Ranney quit his position at the University of Iowa, where he was a tenured professor of urban planning, and moved to Chicago for a job at the Workers’ Rights Center, a free legal clinic for industrial workers run out of a southeast Chicago storefront. When money got tight, Ranney decided to look for work at one of the many factories in the neighborhood. Armed with a made-up work history and a couple of friends willing to act as fake references, he landed a position at a shop that built centrifuges. Over the next seven years, he’d bounce from factory to factory, working at a box maker, a freight car manufacturer, a steel fabricator, and the Solo Cup Company.

Burned out and nearly broke, Ranney eventually made his way back to academia after a chance encounter at a cocktail party led to a position at a community research center affiliated with UIC, where he’s now a professor emeritus.

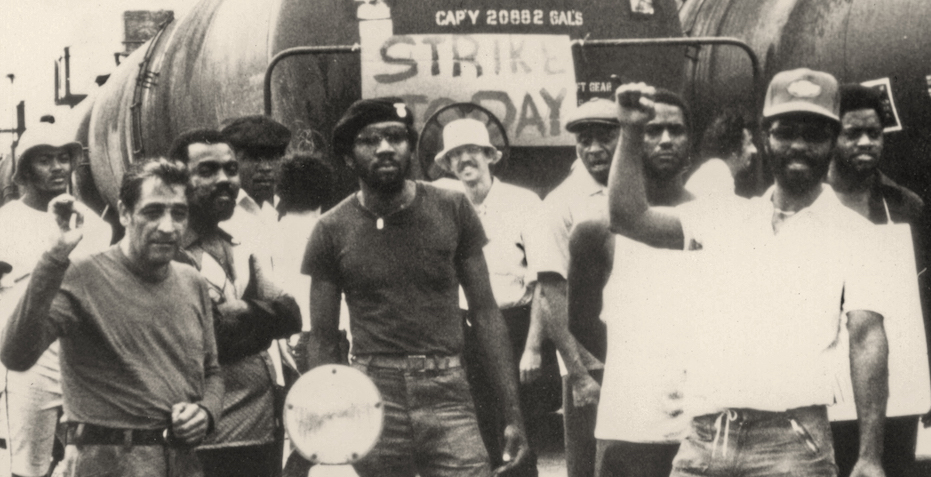

Living and Dying on the Factory Floor, released earlier this month, is Ranney’s account of his time spent laboring in southeast Chicago and northern Indiana. At the heart of the book is the story of a year-long stint at Chicago Shortening, where Ranney helped organize and lead a prolonged wildcat strike. While the strike ultimately failed, Ranney says the experience was illuminating: within the racially charged environment of the factory, the action was able to, however briefly, bring together different groups of white, Black, and Latinx workers in solidarity. At his apartment in Pilsen, where he’s lived for the last 35 years, I spoke with Ranney about Living and Dying. This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

In the introduction, you write that the book isn’t a memoir. Can you explain what you mean by that?

I went to a memoir class, and the teacher said, “Write down three events that you think were transformative in your life. And you have 15 seconds to do it.” So I just jot these down, and they were all deaths. One was a kid that, when I was in fifth grade, got hit by a car. My dad died when I was a senior in high school. But the third one was the death of Charles Sanders. [Sanders was an employee at Chicago Shortening who was stabbed to death by a scab worker shortly after the strike ended.] And that really surprised me, and I realized that his death was about more than just his death although that was very, very traumatic.

You know, he’s a person who had some rough edges, you might say. But during the strike, he sobered up. I never saw him high during the strike. And it meant a lot to him, to stand up to these fuckers.

The things that happened at the plant that really shed a lot of light on the relationship of race and class, immigration policy, class policy, this whole idea about middle-class jobs as seen through the eyes of not just me, but workers that I encountered over a period of seven years. And so that’s not exactly a memoir.

One person at Chicago Shortening that really interested me was Heinz, the avowed Nazi. Can you explain what was going on with him?

Well, Heinz took on all the symbols of fascism, you know. He had swastikas, he had Confederate flags on his jacket and on his motorbike. But he hung out with the Black workers.

And he’d come down the hall and they’d all go “Sieg heil, Heinz, sieg heil!” They’d laugh and so forth. And he was very militant during the strike. He was solidly working class, and he saw all the other workers as his allies. But why he did the other thing? I don’t know. He was just a real contradiction.

You mentioned earlier, and in the book, that you’re really annoyed by the rhetoric around bringing back “middle-class jobs” to the U.S. from some politicians and pundits. What do you mean by that?

It’s not just that we probably will never have manufacturing at the level that we have—there were a million-and-a-half manufacturing workers in the area. It’s also that I don’t want people to have to work at jobs like that. There’s nothing “middle” about it. A lot of it’s really awful.

At that time, workers really could run the factories. I mean, there was enough knowledge there that they could do that. The autoworkers could have run a plant. So one point of view is: OK, workers will take over all these factories and run them. But the other truth is that a lot of them hated their jobs and didn’t want to do that. So what is our goal as radicals: Do we want to help workers run these factories for the other society, or do we want to just get rid of those jobs and get rid of work altogether? At Chicago Shortening it was the second thing—those workers hated that place. They called it “the job.” And they were always doing little petty acts of sabotage, or they were drunk or stoned. They had no desire to, you know, make shortening.

Reading about all the different groups that came out and supported the strike, it seems like there was a really vibrant, if fractured, leftist world in Chicago at the time.

Oh yeah, really, really vicious.

I was in the Sojourner Truth Organization for a time and we had a number of people that worked at a plant called Stewart-Warner on the north side. And every left group had people in Stewart-Warner, because it was one of the few plants where the workers entered from the sidewalk into the plant. And the parking lot was across the street. And so you could leaflet people as they came in.

At the end, all these differences really do come out. This Marxist-Leninist group wrote a critique of how we behaved in the Chicago Shortening strike. It was quite fascinating, really. They were totally critical because, you know, we didn’t see ourselves as a vanguard party and we didn’t take [the plant] over and organize it better. They thought that we had made this huge mistake.

Were you still working in factories when Harold Washington was elected mayor?

I actually left factory work in 1982. But I think that the Harold Washington business—I was working at UIC for that—he did try to see if you could have progressive public policy at the city level. There was one point where, after Wisconsin Steel closed down [in 1980], they had this thing called the Steelworkers Committee to Save our Jobs. And it was organized by a black steelworker named Frank Lumpkin who was in the Communist Party. I did sort of material support, helped them write a newsletter.

They had an ongoing lawsuit, because International Harvester had sold Wisconsin Steel to a firm that had no assets, so they couldn’t be sued. And then they closed the mill and just literally locked the gate. We came up with a proposal that the city would buy the mill, mothball and preserve it, and then sell it once the price of steel went up again, and hire these guys back.

At that time, there was a thing called the Mayor’s Task Force on Steel in South Chicago. I was on one of the subcommittees, but I did have standing to make proposals. So the steelworkers from Save our Jobs Committee asked me if I would go and make this proposal before the task force [on Steel in South Chicago]. So I did, and they didn’t like it. The guy who was the chairman of the committee was Phil Klutznick, one of the biggest developers in the city at the time. And he kept saying, “OK, we’ve heard enough from you, son, we’ve heard enough.” I said, “I’m not finished yet.” I disrupted the meeting.

I went back to the office of Save Our Jobs Committee, and told Frank and the guys that are sitting around what had happened. And Frank says, “Shit, we got to tell Harold about this.” And he picks up the phone and dials and says, “Harold, this is Frank Lumpkin.” He says, “Can we come down? See you in about half an hour? OK, we’ll see ya.” And this says a lot about who Harold was, too, because he was close to these people. I don’t think it was a [Communist Party] thing. I think this Black steelworker was a community leader and Harold respected it.

We went in—he had his office that, for security reasons, had no windows and was completely surrounded by an outer office. When you walk into this room and there’s this desk had absolutely nothing on it but a yellow pad, and Harold was sitting behind the desk. We talked to him for about an hour, and he said, “The thing you guys have to understand is I really don’t have much power. I’m trying, I’m doing my best. But when push comes to shove I doubt they’ll go along with it, and I can’t make them do it.” I thought that was all very insightful.