Freedom: Anarchist News and Views

April 23, 2011

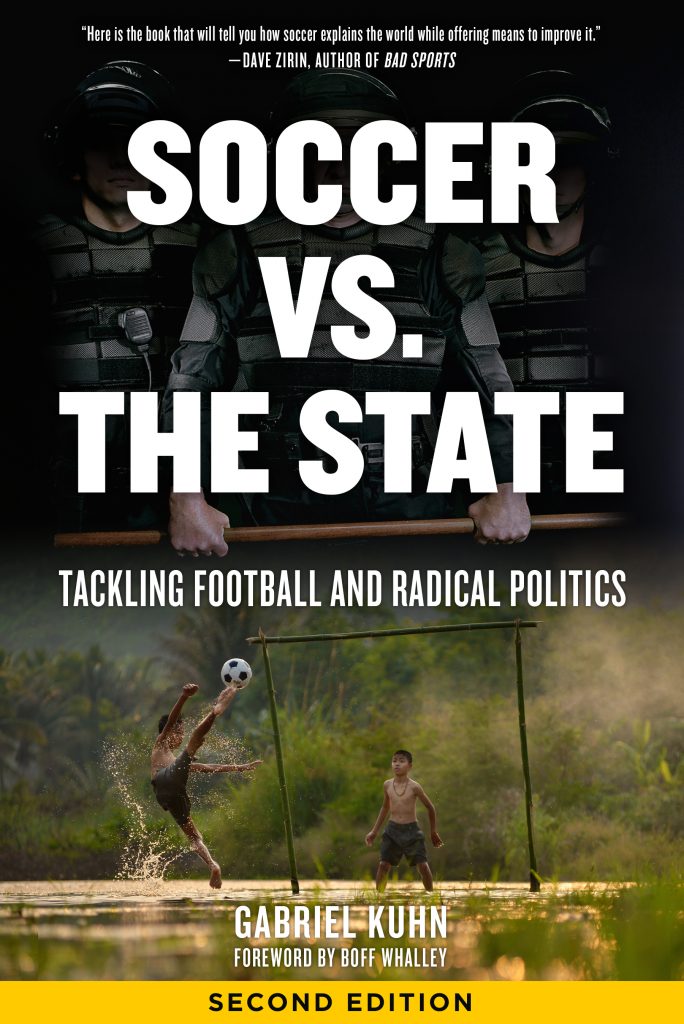

Interview with anarchist footballer and author about the beautiful game: The Austrian-born anarchist author and former semi-professional football player, Gabriel Kuhn, recently released his newest book with PM Press, Soccer vs. the State: Tackling Football and Radical Politics. We talked to Kuhn about football, anarchism, and sports in a better world.

• Is there anything intrinsically ‘anarchistic’ about football?

I’m tempted to say that there isn’t anything intrinsically anarchistic about anything. If anarchy was that easy, we’d have more of it. However, I think that almost everything has anarchistic potential, and it is this potential that anarchists have to tease out. This is also true in football. If you are able to tame the game’s competitive character, football can be a wonderful exercise in community building. If you focus on football’s role as the game of the masses, it can serve as a vehicle to challenge the powerful. If you embrace the beauty and the joy of the game, you reject it as an industry. I would say that it is in this sense that Soccer vs. the State is trying to strengthen the radical—or anarchistic—dimensions of the sport.

• How was football received by anarchism? How could we characterize the relationship between the two historically?

Early on, there was a lot of scepticism within the anarchist movement. The opium-for-the-masses argument was strong, both in Europe and in Latin America. It remained that way well into the 1930s. There is a text in Soccer vs. the State that was published in the 1920s by German anarcho-syndicalists. It basically blames football for distracting the workers from political organizing. Things were never that clear-cut, though. One of the pioneers of soccer in the United States was a Dutch-born IWW activist by the name of Nicolaas Steelink. And during the Spanish Revolution, soccer games were regularly arranged by anarchists in Barcelona.

Today, soccer might still be eyed sceptically in some anarchist circles, but overall I think the reception has changed. Particularly in North America, soccer has become really popular among anarchists. I guess it is mainly the internationalism that is appealing. We must not forget that conservative U.S. talk show hosts like Glenn Beck still blasted soccer as un-American during the 2010 Men’s World Cup. Also in Europe and Latin America, increasing numbers of closet anarchist football fans have come out into the open. The FC St. Pauli phenomenon certainly had a huge impact. Since a bunch of squatting punks and anarchists took over the St. Pauli stands in the mid-1990s it has become significantly easier for anarchists worldwide to relate positively to the game. I welcome this development, of course. Football plays a huge role in communities across the world, and it’s important that anarchist voices have a presence.

• Where did the perception of football as twenty-two cretins chasing a lump of leather come from? Was it always thus? How did it become the preserve of the working class?

Since football has always been popular with the masses, it has always had to endure the ridicule of the cultural elite. This is true for every pop cultural phenomenon. There also exists an intellectual arrogance, often expressed in the form of a general disdain for physical exercise and play. Needless to say, such attitudes are rather silly. We must not let them bother us. Who cares what self-appointed cultural and intellectual elites think? The reason why football is so popular with the working class is probably simple.

Football is a straightforward game that doesn’t require much equipment. It can practically be played anywhere and under all circumstances. This also gives it a distinctively democratic character. For more than a hundred years, football has been one of the few social fields in which class differences haven’t necessarily translated into a disadvantage for the poor and underprivileged. The development of a football player is far less dependent on economic resources than the development of, say, a tennis player or a golfer. Nor does a lack of formal education give you less authority in discussing the line-up and the tactics of, say, the English national team. It is largely these aspects that give football its unrivalled global role as the people’s game.

• How did capitalism take over football…was it inevitable?

Perhaps it was inevitable in the sense that capitalism is taking over everything that promises profit. However, capitalism has never been completely distinguished from football. If we look at the origins of many of the leading clubs in the late nineteenth century, they were already exploited by companies and factory owners, at least for prestige. So the ever increasing commercialization we have witnessed in the twentieth century was not the result of an outside force but of an intrinsic logic, if you will.

Over the last twenty years, the commercialization has taken on a particular momentum. Football has turned into a spectacle that people could have hardly foreseen when World Cup Willie was sold as the first official World Cup mascot in England in 1966. Champions Leagues, a 32-team Men’s World Cup roster, multi-billion dollar TV contracts, celebrity players, and a ruthless merchandise industry that doesn’t even stop short of selling corporate-sponsored jerseys to the average football supporter are all expressions of this. Hardly any of it can be encouraging for a radical football fan.

For me, the response has to be two-fold. Within the professional game, we have to campaign against the exploitation of both spectators and players—and I’m not talking about the obscenely rich top 0.5% of professional players, but about the tens of thousands of football professionals who live under precarious conditions, particularly migrant players from Africa. Within the world of football in general, it is important to support grassroots initiatives that do not only promise all the fun in a politically sound and non-commercial environment but also create opportunities for effective community organizing and everyday political activism.

• Can you give examples?

I think you find one of the best in the UK with the Easton Cowboys and Cowgirls Sports Club hailing from Bristol. The Easton Cowboys and Cowgirls have managed to form local alliances that many political organizations can only dream of and to establish worldwide connections that translate directly into international solidarity work. There is an excellent article about the Easton Cowboys and Cowgirls included in Soccer vs. the State, written by Roger Wilson—I really encourage everyone to read it!

• Why did football become so macho . . . was it always so?

Especially in the UK, women’s football became really popular during World War I. In 1920, the best women’s team at the time, the Dick, Kerr’s Ladies, played their main rivals, St. Helen’s Ladies, at a legendary game at Liverpool’s Goodison Park in front of a crowd of 53,000. Soon after, the English FA officially banned women’s football. Many other national FA’s followed suit. A great number of these bans weren’t lifted before the 1970s. This halted the development of the women’s game for fifty years and effectively turned football into a men’s only affair. These bans marked perhaps the single most scandalous chapter of football history and reflected the deeply rooted patriarchal structures that have haunted the game from its beginnings. Luckily, things have changed in the last twenty years—slowly but steadily. There remains a lot to be done, though, both in strengthening the women’s game and in erasing sexist attitudes from the men’s game. In terms of heteronormativity, the struggle has only just begun. It will be a long but terribly important fight to rid football of homophobia!

• Where have the changes come from?

Social movements have been a big factor, as always. Groups that had long been excluded from football started demanding their place: women, people of color, gays and lesbians, people with disabilities, and others. Another factor is that forms of oppression have become more flexible. Traditionally excluded social groups are increasingly wooed as consumers. The trend to turn football stadiums into shopping malls reflects this. It is a development that does have certain progressive dimensions as it allows a number of people to feel comfortable in a space that didn’t feel very welcoming before. However, these forms of increased inclusion are offset by new forms of exclusion, mainly economic ones. What we really need is social change apart from corporate interest.

• Are there any major ‘left-wing’ teams today?

The way professional football works today, I don’t think you can be major and left-wing at the same time. There are some big clubs—the FC Barcelona probably being the most prominent example—that stand for values such as independence, social awareness, and participatory democracy. However, the money and the power involved, the demands of success, the unsettling notions of loyalty and rivalry—none of this sits well with what I see as the core values of left-wing politics, namely justice and solidarity. But this doesn’t make the progressive elements less valuable, nor does it mean that anarchists can’t enjoy football on the highest level. The challenge is to bolster the left-wing dimensions that exist and to oppose those that reflect and perpetuate an unjust political and economic system.

• How can we as anarchists develop football?

On the professional level, we can campaign for more democracy within the football associations, for more supporter influence, for a more inclusive environment, for less corporate control, for players’ unions, and for a just division of resources, including equitable salaries. On the grassroots level, we can strengthen the communal aspect of the game, keep the competitiveness at bay, and meet all players with respect. At the risk of sounding moralistic, I also believe that notions of fair play are important: so-called tactical fouls, diving, trash talking, etc. have no place in radical football, no matter the level.

• Which team do you support? How do you justify it?

I guess I’m in the lucky position that the Nick Hornby model of never-ending devotion to your childhood team doesn’t apply to me. There really isn’t any particular team I support; it’s more of a game-to-game decision. This also means that I’m fairly flexible with my justifications. As for many people, rooting for the underdog is a common choice. Other choices are supporting a team that represents a community I sympathize with or that has players, managers, or fans I like. The only irrational obsessions I keep concern teams I have always disliked: Bayern Munich and the German national team. I seem to have a hard time getting over that.