By Luke McGowen-Arnold

Chicago Review of Books

An essay about Black Resistance, Imperfect Utopias, and Terry Bisson’s “Fire on the Mountain.”

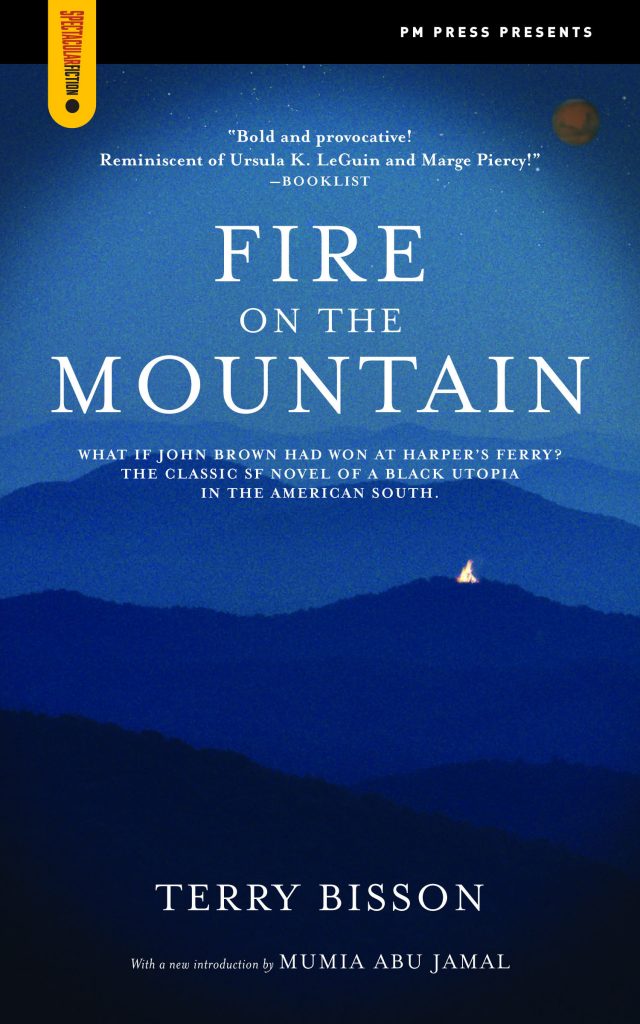

Terry Bisson’s novel Fire on the Mountain ends with a spaceship landing on Mars. Unfortunately for us, humans landing on Mars at the moment is largely a dystopian nightmare promulgated by the wannabe god-king tech billionaires such as Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, or Marc Andreessen. But in Bisson’s novel, it is a different story. A different timeline in fact. It is 1959. The people landing on Mars are communists, not capitalists. It is one hundred years since John Brown launched his raid and succeeded in inciting a guerrilla war on behalf of the slave. The novel hinges upon Brown’s success after he decides to bring Harriet Tubman along with him on the raid. Instead of being caught, they escape into the mountains. Eventually, they are joined by the slaves and ignite a conflagration that ends with an independent Black socialist republic in the Deep South called Nova Africa, a clear nod to the Republic of New Afrika, a Black nationalist movement founded in 1968 that desired the five states in the South as reparations in order to constitute an independent Black republic. The origin of the modern reparations movement comes from the RNA’s legacy. Alternative history novels like Bisson’s can help us understand the possibility of resistance and liberation in our current moment.

Black resistance is rarely exalted in literature let alone in alternative history. As a genre in the American context, the genre often tells stories about Black people remaining enslaved or shackled under the South’s racial order. A few years ago, I read Biography of X by Catherine Lacey. Lacey’s novel depicts an alternative timeline where the South secedes suddenly in 1945 and builds a deeply repressive society in contrast to a social democratic North. Noticeably though, Black people and their resistance are largely absent. In contrast, Fire on the Mountain Black people build a Black socialist republic while the North lags behind socially and economically.

Main mainstream novels written about Black people generally are narratives of victimhood, so Fire on the Mountain is a refreshing exception. Southern Black people, or n’Africans as they are called in the novel, fight for their own self determination. The book also highlights how the white power structure underestimated the slave’s willingness to fight for their freedom. While Brown and Tubman’s raid acts as a catalyst, the novel depicts numerous slaves taking part in varying acts of resistance. Slaves join Brown’s Army of the North Star, burn their master’s plantation, facilitate escapes, bury the dead revolutionaries, and smuggle supplies to guerrillas. These acts of resistance are not imaginary however, they are all sourced from history however Black resistance is generally neglected in fiction. As an example, In the final stages of the Civil War, slaves took part in a general strike that crippled the South’s economy as described in W.E.B. DuBois’ book Black Reconstruction. So while Fire on the Mountain is a fantasy, there are grains of truth.

As I read the novel, I was consumed by feelings of deep melancholy and longing for the world that the characters live in. Bisson uses the literary device of a novel within the novel. The characters living in the 1959 are aghast at our world where “the slavers began the war” and where “white supremacy won.” The fictional novel is a critique on our current reality from characters in the Black utopia. The book is brilliant as it hits hard at narratives of American democracy as progressive in regards to how many American liberals think about the Civil War as a victory for democracy and racial justice. Instead, the characters talk about how the Black population was repressed and then became servant classes in the Industrial north. In many narratives, the Great Migration north is viewed as a progressive moment in history for Black people. The character’s understanding the “victory” in the Civil War was hollow brings an interesting new perspective for us to think about.

Our reality now is a bleak one compared to Bisson’s 20th century. Our lives are filled with horror and uncertainty. And literary fiction often works better depicting those things, at least for me, than a lot of contemporary science fiction that often reads as escapism. In a refreshing way, Bisson’s novel feels incredibly American despite the fact that it castigates the racial capitalist order of the United States. Frederick Douglass makes an appearance where he exhorts his followers to support Brown’s guerrilla war struggle and escapes Federal marshals attempting to arrest him due to his support for Brown. Marx raises a regiment in England to support the war for n’African independence. An alternative version of Abraham Lincoln is racist who fights a war to bring Nova Africa back into the capitalist North. These countless references show how Bisson is tapped into the bloody histories of the States which grounds the whole text deeply in reality.

Contemporary fiction with speculative, afro-futurist, or utopian themes often feel utterly divorced from our current moment, so to read Fire on the Mountain was refreshing as it roots the narrative deeply in American historical and present. Our current reality is so horrid, it is difficult to imagine anything other than an AI apocalypse, nuclear war, white supremacist purges, or another pandemic. Imagination and dreams of a utopia often feel as if they are the domain of disconnected writers. This is partially why I have largely avoided reading science fiction for the past five or so years because much of it feels utterly separate from the daily horrors of today. Alternative history works interestingly in this space as it draws deeply from our blood stained history. Towards the end, one of the characters, a young escaped slave Abraham, recounts watching the red, black and green banner fly as Brown is buried atop one of the Blue Ridge mountains. And then the war continues. A thousand more losses and deaths are sustained before liberation. The book is not utopian in that sense.

While it depicts a world that is far more utopian than our world, it is not perfect. One of the narrators, Yasmin, a Black communist, encounters a white racist woman who still harbors hatred of Black people despite a revolution transforming the United States into the Socialist United States. Yasmin’s husband died in the first mission to Mars. Much of the novel explores her grief around his death and her disconnection with her daughter because of that grief. Even in Black socialist utopias, human beings are still fraught with pain. The idea of an imperfect utopia is common in left leaning fiction as the narratives grapple with human pain in a society where much of social pain has been abolished. Fire on the Mountain is a novel in the canon of the “imperfect utopia.”

Another author who works well with the idea of the imperfect utopia is Ursula K. Le Guin. Her novel The Dispossessed depicts an anarchist society that despite being far better than our own, the characters face the struggles of being human which she describes as separate from the social suffering imposed by CEOs, kings, ICE agents, slave owners, the police and all others who seek to oppress others. One character describes this in the novel:

Suffering is the condition on which we live. And when it comes you know it. You know it as the truth. Of course it’s right to cure diseases, to prevent hunger and injustice, as the social organism does. But no society can change the nature of its existence. We can’t prevent suffering. This pain and that pain, yes, but not Pain. A society can only relieve social suffering, unnecessary suffering. The rest remains. The root, the reality.”

The description of suffering as “the root, the reality” while the social organism can cure hunger and injustice is a fascinating idea. This is the case in Fire on the Mountain as the society has moved beyond a racial capitalist society and much of the social suffering. However, the condition of suffering is present in Yasmin’s struggles to connect with her daughter, the heartbreak experienced by historical abolitionist Thomas when he learns his best friend is involved with a woman he’s in love with and escaped slave Abraham’s sadness with his brother’s death (he does not learn that the person who dies is his brother until after his death at the hands of the white counter-revolutionaries) while not wholly separate from the social suffering are human experiences that continue regardless if we end oppression. Pain remains. The beauty of Bisson’s book is how we can read about a Black socialist utopia where people still love imperfectly despite their ability to transform their conditions.

In our current moment, it feels impossible to imagine a better world. And yet, resistance grows everywhere in small ways. Books such as Bisson’s can light the way. At one point in the novel, an older enslaved woman talks about the fires lit by the guerrillas on the mountain:

Fire on the mountain,” the granny woman said. “They up there sharpening they swords.” Then she said that word again: freedom.

The imagery of the fire on the mountain lit by the Army of the North Star serves as a reminder and inspiration to the slaves that the enduring fight for freedom has not ended. A small motley but determined crew of rebels changed the world in Bisson’s novel. The scale of the problems we face seems insurmountable but small groups can change the course of history. Slavery once seems never ending and now it is over. Resistance and social transformation is always possible. We should remember that.