The art of the essay provides a platform for writers to share their subject and perhaps a bit about their worldview. We read essays all the time, usually as reviews, mainly on books, movies and music. And there are notable collections such as Pauline Kael’s oeuvre. A writer who likes to write such essays tends to like a lot of things and Franklin Rosemont (1943-2009) was no exception. Rosemont was passionate about the masses, mass media and how it all interconnected. In this collection, the reader is swept up by Rosemont’s thoughts and vivid writing on the inclusive power of entertainment, particularly, cinema, comics, Surrealism, and popular music.

Beginning in the 1960s, and for the next thirty some years, Rosemont wrote and edited for progressive magazines, the two main ones being Cultural Correspondence (1975-1983) and Radical America (1967-1999). It seems only natural that Rosemont made connections with the Left, especially the Labor movement, and the democratic nature of mass entertainment. Anyone is free to enjoy it, to contribute to it, to be transformed by it. As I read one essay after another, I was moved by the cumulative effect of Rosemont’s arguments, his deep belief that everyone has a place at the cultural table.

“The Dream That Came True,” by Dust Wallin, One Big Union Monthly, May 1920.

Mad Magazine, May 1, 1954. Basil Wolverton. As subversive as he needed to be.

The more I read, the more I gave myself over to the people power theme in these essays. It certainly fits in well with Rosemont’s writing on cartoonists for Wobbly newspapers, like Industrial Worker (1909-1931). But can one be certain that Basil Wolverton (Mad Magazine, 1950s) was so closely aligned with the proletariat, as Rosemont seems to imply in another essay? Well, maybe so but you just never know for sure. The greatest satirists will leave you wondering which side they’re on, if any. Of course, one can argue that anything unusual in the 1950s potentially carried subtext. It is a different case with the Surrealist movement which, beginning with its founder, Andre Breton, made clear it was indeed an anti-fascist movement. It’s interesting to consider Surrealism’s history, starting in 1924 and into the 1950s. What began as an art and political movement, in response to the aftermath of World War I, was constantly pushing against authority. In this context, it is not surprising to bring in the subject of anarchists. One of Rosemont’s most insightful essays discusses how the anarchist political and philosophical movement, focused on the viability of stateless societies, came to be maligned in the United States and caricatured as bomb-toting terrorists.

It’s the 1920s, the era of silent movies, where I will conclude my review. If we are looking for connective tissue to Rosemont’s writings, we need look no further than dreams. It is in the land of dreams, after all, that we can all indulge our most subversive desires. We can all return to our youthful ambitions of leading the charge in the subculture! It is the world of silent movies, with its play of light and shadow and uncanny expression that we enter a netherworld closely aligned with our own private slumberland. In this world, such figures as Buster Keaton, the Great Stone Face, reign supreme. No wonder such a world would utterly fascinate Rosemont and lead to some of his most compelling writing. Here is an excerpt:

These two films (Sherlock Jr., 1924; Cameraman, 1928) best exemplify Keaton’s revolutionary/poetic worldview. When he passes through the looking-glass, he is not content merely to see what is on the other side: he braves his way through a whole succession of looking-glasses, each behind the other, and each reflecting only the meagerest hint of what we call “the real.” And what motive could possibly underlie such feverish wanderings back and forth through the interpenetrating spheres of the pluriverse? The answer is crystal clear: Keaton’s audacity is in the service of sublime love. His agility is always radiant with a lover’s grim determination. There is no risk that he will not take for the woman he loves. Only Buster Keaton, moreover, can sustain a single kiss for two years (The Paleface, 1921).

We can always return back to Keaton, with that iconic poker face, champion of subversion but always leaving you to wonder as to what side he’s on, if any. When I simply consider Keaton’s artistic considerations, I feel confident he was seeking a more universal tone with whatever he did. Let his movies speak for him, he would say. Ah, there’s that one scene with Keaton (Cops, 1922) when he takes a bomb, by then popularly accepted as the symbol for the anarchist or, more plainly, widespread mayhem, uses it to light his cigarette, and then throws it back to the police. A great political statement? Hmm, how about just a funny visual prank? The Great Stone Face would never tell.

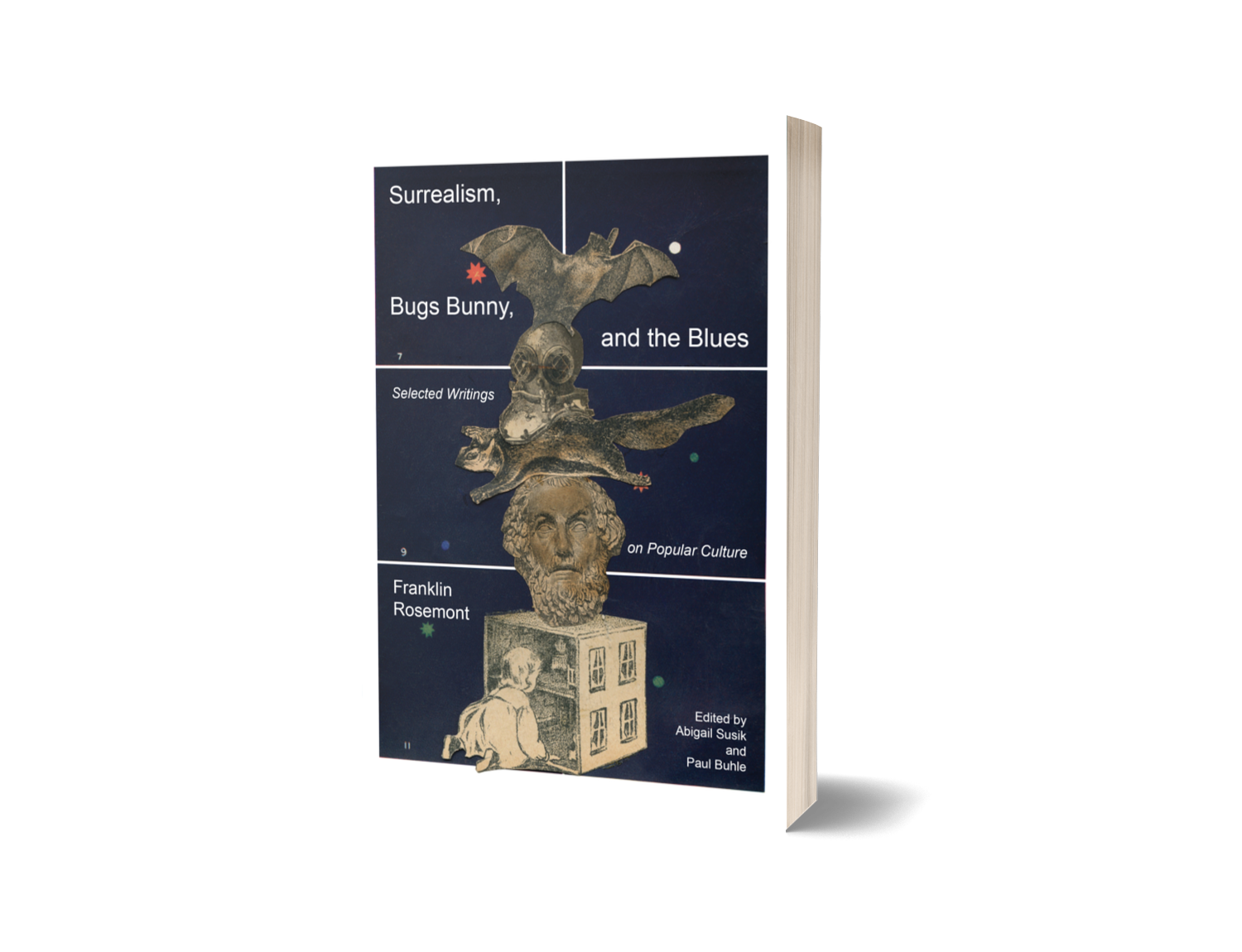

Like any great collection of essays, there is something for everyone in this book. Give yourself over to the vast array of subjects discussed here, and you’ll be the richer for it. I can imagine Rosemont going from one cultural signpost after another and reaching his own conclusions such as embracing Bugs Bunny as a folk hero for the masses. Well, more than fair enough. And he takes it one step further and implicates Elmer Fudd. Again, more than fair enough, as well as relevant for today. Yes, be wary of the Elmer Fudds of the world, those who only think in terms of transactions. The Fudds of the world are the conformists and the sell-outs. But, with will and determination, the Bugs Bunnies of the world will prevail!