Review by Gertrude Fester

New Agenda

Dr Gertrude Fester, a former MP and Gender Commissioner, is Honorary Professor at the San and Khoi Research Unit and Centre for African Studies, University of Cape Town. She was a long-standing member of the United Women’s Organisation (UWO) and United Women’s Congress (UWCO) and worked with women in the informal settlements of KTC, Nyanga Bush and Crossroads.

Dr Gertrude Fester, a former MP and Gender Commissioner, is Honorary Professor at the San and Khoi Research Unit and Centre for African Studies, University of Cape Town was a long-standing member of the United Women’s Organisation (UWO) and United Women’s Congress (UWCO) and worked with women in the informal settlements of KTC, Nyanga Bush and Crossroads.

A lifestyle agency in 2018 advertised a house in Cape Town’s mega-fancy suburb of Fresnaye for a monthly rent of R175,000 belonging to President Cyril Ramaphosa. “you may even catch a glimpse of the president.” He lives in his private house next door on the R30 million plot.1

The above exemplifies the contradiction of this “world class city” which has won many accolades

__ a foremost city in a country which is number one in terms of the ginicoefficient (which measures inequality). This contradiction is what author Koni Benson, her talented illustrators, André Trantraal, Nathan Trantraal and Ashley E. Marais and the diverse teams with which she has worked for the past 15 years clearly expose after analysing and examining the housing struggles in Cape Town of poor people in a city which is also characterised as a playground for the rich.

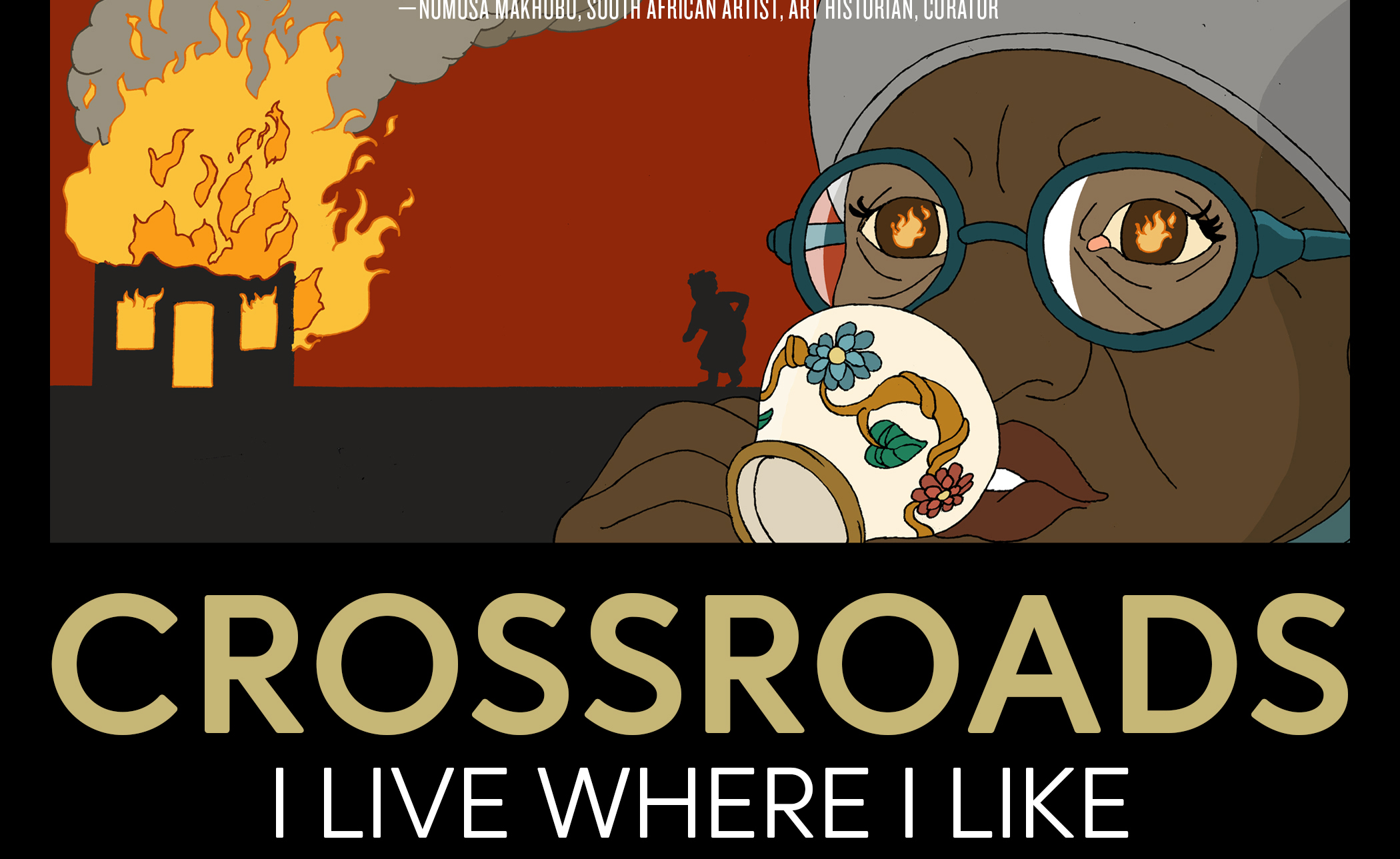

I need to laud this courageous and innovative task by Koni and her three artist collaborators as an excellent work of art, a textbook, a popular education tool, and a work of “graphic non-fiction”.

The foreword, by Robin Kelley, describes reading this book as a highlight and as one of two close encounters of real people’s history in his life. Koni stresses that Crossroads was the only informal settlement that was not successfully demolished. 2 The introduction by Koni outlines the aims and the dynamic and admirable process whereby this book was created.

This example of graphic non-fiction, based on Benson’s PhD, is one of the very few doctoral theses that is not just lining the library shelves of academic institutions. As a historian committed to creative methodologies of popularising history and struggles, she successfully combined her interests: people’s history projects, popular education and feminist collaborative research praxis in her work at various levels, archival research. She worked with diverse students, activists and cultural collectives in Southern Africa to create this valuable contribution to popular education and community awareness-raising.

This book is not only phenomenal in its innovative format as “graphic non-fiction” or a “cartoon on women’s struggles” but also in the way in which content has been compiled and written. A series of consultations took place with community activists and structures.

Through several workshops participants delved into and analysed the racist and sexist history of Cape Town and how it expressed the manoeuverings and manifestations of how capitalism works. It is a production, and continuous re-creation, of the current housing crisis, which started decades ago and continues today.

It must have been an enormous challenge to transform the material of the PhD of Koni Benson into

accessible and easy-to-read dialogue and explanatory notes. It has given me insight into the difficulties of balancing image and text, and how to make text complement the image and vice versa.

Also challenging is how and when to deal with problematic concepts. During the research for her work Koni collaborated closely with the International Labour Research and Information Group (ILRIG), with housing activists, and with community organisers mobilising around housing issues which included xenophobia, sexism and racism, water cut offs, current evictions and homelessness.

The consultations were not just one-off, but rather included a longitudinal study: workshops and courses of a 2011/2012 People’s History course; a 2012/2013 Community Activist course; and discussions from the 2006-2011 monthly women-only public forums with activists from housing, food, water, domestic workers, sex workers, migrant labour and refugee organisations. The list of organisations is formidable, ranging from the Progressive youth Movement to the Delft Integrated Network. Questions deal with how the city had been constructed/de- and reconstructed, exploring histories of mobilisation/demobilisation which were utilised effectively in understanding strategies for struggle and for exploring various mechanisms: how struggles and movements are potentially undermined by reactionaries albeit at the same time as being lauded in general.

Chapter 1 provides some historical background, quoting jan van Riebeeck and material from his journal. It illustrates the agency and power of black people. I do think, though, that the date the Nationalist Party came to power should have been mentioned as well as an explanation of what the passes meant to people’s lives. There is also a mention of Khoi once without any reference to who and what they were. Furthermore, the coloured labour preference policy should have been explained earlier, hence giving a context to the forced removals. This made me question who was the intended target audience for this book.

Chapters 2 and 3 illustrate the creativity, organisational skills, and the strategic action of the women in building networks with progressive organisations and individuals outside the township.

Throughout the book the strength, unity and peace the women were trying to build for the good of the community is juxtaposed by the power of the patriarchy, patronage, greed and divide and rule strategy of the apartheid authorities, the undermining of women and the violence and burning of houses.

The euphoria surrounding the events in macro South Africa from 1990 to 1994, around the negotiations and the eventual elections in 1994, contrast starkly with the micro image of the lived reality of the people of Old Crossroads. The emergence of the Women’s Power Group once again illustrates the resilience of the women. This chapter is paramount in exposing the complexities of the South African struggles and the invisibility of marginalised women such as the women of Crossroads. This final chapter again illustrates the patriarchal vying for power and support, not by warlords but by political parties, the ANC and PAC.

The artwork is vivid and dynamic, effectively capturing emotions, expressions and atmosphere. Use was made of images, photographs and general media. The complementing of the images by the text is well done and relevant. In some cases, when historical background is required, the text is dominant. I could only access the electronic PDF version, which may be why I found the use of the font and capital letters not always clear.

As much as this book is about highlighting the agency and power of women, it also illustrates the ongoing struggles of women in this “new South Africa”. The use of people’s actual names

and words give an added poignancy and authenticity to the text. The book ends with the words of Nosisi Mbeka: Us people in Boys Town, we are still in the apartheid time. I can’t say I’m in ten

years of freedom. I’m in ten years of struggle.

Crossroads is published in the USA and is available from https://pmpress.org.

ENDNOTES

- See www.times live.co.za accessed 26 March 2021.

- KTC was also never successfully demolished. Women demanded land and housing and got what is today Tambo Village. For example, they designed and named the streets after their comrades, jenny Schreiner and Ivy Gcina.